Having looked into our explanations of transformations and symmetry, over the last weeks, let’s turn to the recent questions that triggered this series. Here we have an adult studying the topic from a good book, but tripping over some issues in the book. We’ll be touching on some topics we haven’t yet looked at, such as using coordinates for transformations, and notation.

Rotation … around a different point?

The first question, from the end of December, deals with formulas for rotation in terms of coordinates, something we haven’t touched on yet:

Hi,

I am working my way through the book “Barron’s Math 360: A Complete Study Guide to Geometry.” When it discusses the rotation of figures on a coordinate grid, I think the book has made a mistake or I am not understanding it correctly.

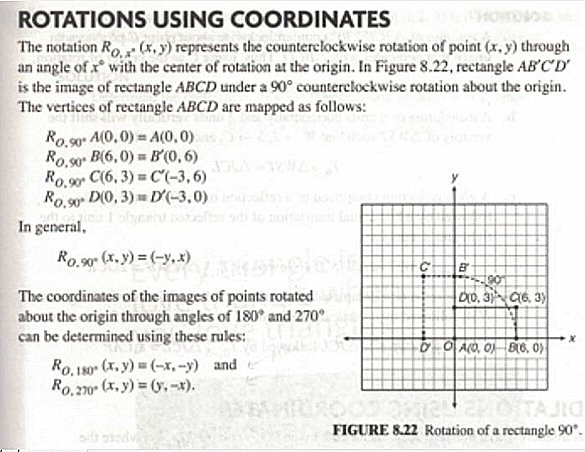

As an example of rotation, we are shown a rectangle (ABCD) that is rotated 90 degrees counterclockwise (AB’C’D’). The example gives the coordinates of each point, both before and after the rotation, then states a general rule for 90 degree rotations:

RO,90° (x, y) = (-y, x)

All of this so far is correct; the general rule works for the example given.

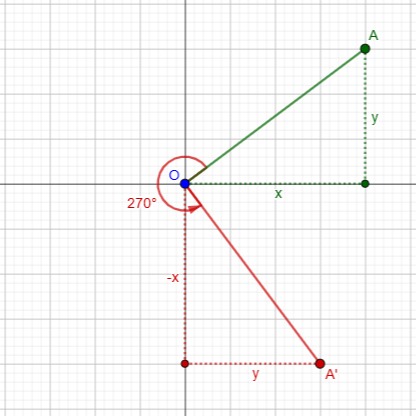

The notation represents rotation of, for example, the point \(C (6,3)\) to \(C’ (-3,6)\). Using color to emphasize the original and transformed objects, we have

.This is a rotation by 90° counterclockwise.

The formula they give for a 270° counterclockwise rotation, which we’ll be doing (which we could also think of as 90° clockwise), works like this:

We start at \(A(x,y)\) and rotate to \(A'(-y,x)\), because the vertical side of the green triangle becomes the horizontal side of the red triangle, while the horizontal side of the green triangle becomes the vertical side of the red triangle, pointing down. (This is closely related to the fact that the slopes of perpendicular lines are negative reciprocals.) Once you learn trigonometry, you can do this for any rotation angle: \(R_{O,\;\theta}(x,y)=(x\cos\theta-y\sin\theta,x\sin\theta+y\cos\theta)\). In this book, however, the notation is only used for the three special angles.

Continuing the question:

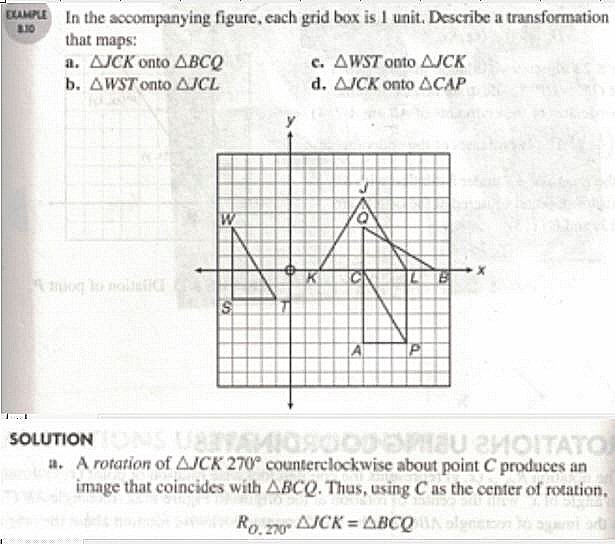

But in “Example 8.10,” question (a) asks a question whose answer is a counterclockwise rotation of 270 degrees. Triangle JCK is rotated to triangle coordinates BCQ. The “Solution” given for question (a) is correct. Yet the general rule given for rotations of 270 degrees

RO,270° (x, y) = (y, -x)

. . . does not work. J(5,5), C(5,0), K(2,0) is rotated to B(10,0), C(5,0), Q(5,3). But according the general rule for 270 degree rotations, the BCQ coordinates should be B(0,-10), C(0,-5), Q(3,-5).

So what is going on here? Are the given general rules for rotations of 90, 180, and 270 degrees correct?

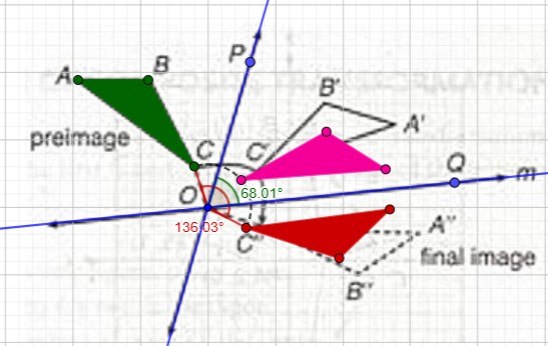

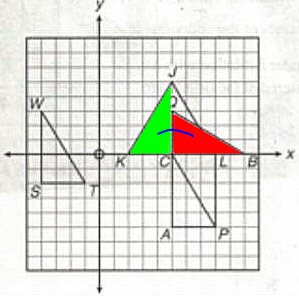

We want to rotate \(\triangle JCK\) to \(\triangle BCQ\) as shown here (marked as a 90° clockwise rotation):

Note that it is pivoting around point C. Jim recognizes that this is the intended rotation, which was all the question wanted; but what about that formula they taught?

Doctor Rick answered:

Hi, Jim.

The rule you cite is for rotation about the origin. In this problem, the rotation is about the point C. That’s the difference.

I don’t know how this is taught in your source, but one way to accomplish what we want here is to first translate (shift) each point 5 units to the left (so that C is moved to the origin), then rotate the point about the origin, using the formula you were given; and finally, translate it back, 5 units to the right, returning point C to its original place.

The book never states how to handle the coordinates of a rotation about a point other than the origin, O. And the question didn’t ask us to apply the formula, just to identify the transformation. But their answer uses the wrong notation, \(R_{\textbf{O},270^\circ}\) instead of \(R_{\textbf{C},270^\circ}\), making it look as if their formula should apply; which leaves the reader dangling, wondering how everything fits together.

Doctor Rick’s approach is standard: Since the provided formula applies only to rotation around O, if we want a formula, we have to treat this rotation as a composition of a translation to the origin, a rotation there, and a translation back: $$R_{P,\;270^\circ}=T_{O\;to\;P}\circ R_{O,\;270^\circ}\circ T_{P\;to\;O}$$

This could be combined into a slightly unwieldy formula:

$$R_{(a,\;b),\;\;270^\circ}(x,y)=T_{a,\;b}\left(R_{O,\;270^\circ}\left(T_{-a,\;-b}(x,y)\right)\right)\\=T_{a,\;b}\left(R_{O,\;270^\circ}\left((x-a,y-b)\right)\\=T_{a,\;b}\left((y-b,-(x-a)\right)\right)\\=(a+(y-b),b-(x-a))$$

For example, $$R_{C,\;270^\circ}(J)=R_{(5,0),\;270^\circ}(5,5)=(5+(5-0),0-(5-5))=(10,0)=B.$$

Composite reflections … is the picture wrong?

A few days later, he had a question about composition of reflections:

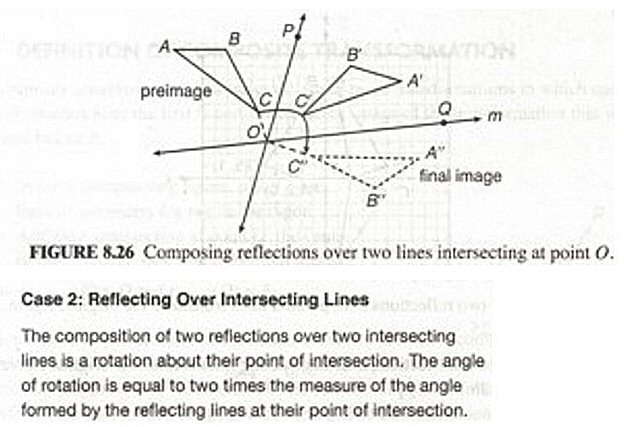

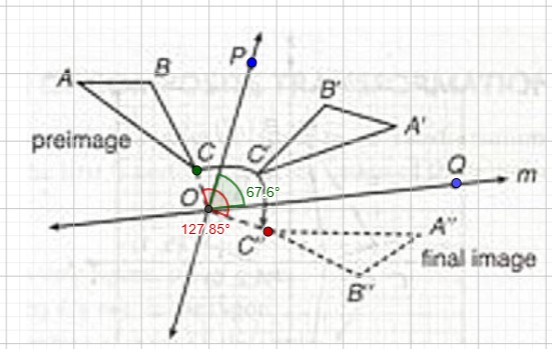

Figure 8.26 shows two reflections of triangle ABC over intersecting lines.

The intersecting lines contain points P and Q. (The line with point Q is given the name of lowercase m; the line with point P is missing a name, though elsewhere in the book such a line would be named lowercase l. Perhaps there was no room for it in the image.)

The reflection goes from preimage ABC to intermediate image A’B’C’ to final image A”B”C”. These two reflections can be seen as a rotation of the triangle about center of rotation O.

The paragraph titled “Case 2: Reflecting Over Intersecting Lines,” gives a verbal description of an equation that applies here:

“The angle of rotation is equal to two times the measure of the angle formed by the reflecting lines at their point of intersection.”

Does this mean angle COC” = 2 x angle POQ? If so, that does not seem to be what Figure 8.26 shows. I used a protractor to try to measure the angles in the figure. I got 130 degrees for COC”, and 70 degrees for POQ.

We saw this idea in Slides, Turns, and Flips: How to Combine Them.

He soon added,

Okay, so with my protractor I re-measured POQ and now get 68 degrees. That’s getting close to a correct equation, so maybe the figure just isn’t exactly correct, or trying to measure its angles with a protractor is futile, or my vision is failing me.

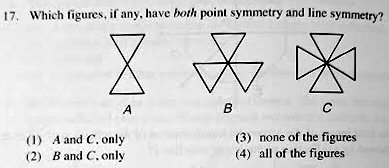

I measure the angles as 68° and 128°, using GeoGebra:

But \(2({\color{DarkGreen}67.6})=135.2\ne{\color{Red}127.85}\).

I answered:

Hi, Jim.

The picture is horrendously inaccurate! You can see that by measuring other aspects of it, to see whether each triangle is actually reflected as stated.

Notice, for example, that C and C’ are not the same distance from line OP, on a line perpendicular to it, as reflections must be.

Here is an accurate version, made with GeoGebra:

I hope the book not only makes the statements you quote, but also proves them, showing why they must be true! You should see that, for example, angles COP and C’OP are congruent, as are angles C’OQ and C”OQ. This is why angle COC” is twice angle POQ.

They don’t prove this; but then, I didn’t bother to do so either, because a good picture makes it easy to see why! A bad picture, on the other hand, does not.

Jim replied,

Thank you, Dr. Peterson, for your quick and helpful answer! The book I’m using has at times been skimpy on explanations and at times even a bit misleading, but I’ve managed to understand what was meant or should have been stated. But this time it was too much for me. Your reply to my question makes perfect sense.

In preparing this post, I discovered that the same book was in my local library, so I got it; reading between the snippets Jim had sent, I see that it is a good book, and this (and its partner with parallel lines) seem to be the only images that are so poorly done! As a study guide, it doesn’t go into depth on every detail, but I think it’s a good effort. Any book sometimes needs a little human supplementing; that’s what the Math Doctors, like the tutoring center I work at, are here for!

Point symmetry … is the book wrong?

A few days later, we got into symmetry:

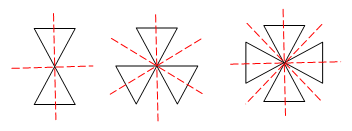

For question #17, the book I’m using says the answer is (4). But it seems to me that figure B does not have point symmetry and has only vertical line symmetry, not horizontal line symmetry.

For point symmetry we’re told that “if you’re not sure whether a figure has point symmetry, turn the page on which the figure is drawn upside down. Now compare the rotated figure with the original. If they look exactly the same, the figure has point symmetry.”

The original figure I see has 1 triangle on top, 2 on bottom; the rotated figure has 2 triangles on top, 1 on bottom.

I think the correct answer to question #17 is (1). Am I mistaken?

Note that they treat point symmetry as identical to 180° rotation; we saw last time that although that is true, there is a reason for giving it its own name.

Doctor Rick answered:

Hi, Jim.

You’re right: figure (B) does not have point symmetry. As the other page says, point symmetry is the same as 180° (or twofold) rotational symmetry. Figure (B) has rotational symmetry, but 120° (threefold), not 180°. Perhaps the problem was misstated and was intended to say “rotational” rather than “point” symmetry.

As I explained in From Transformations to Symmetry, the meaning of point symmetry is a reflection in a point, but that is equivalent to a 180° rotation. Focusing on the rotation perhaps led to some confusion in the writing either of the problem or of the solution (which may have been by different people).

Jim thanked him, and Doctor Rick added a little more:

You mentioned in your initial question that “figure B … has only vertical line symmetry, not horizontal line symmetry.” In case it wasn’t clear, I want to note that the problem only asked whether each figure has “both point symmetry and line symmetry”, not how many or which line symmetries they have. Figure B is not ruled out on this score, but only because it does not have point symmetry (symmetry under reflection through a point).

Horizontal and vertical lines of symmetry are not the only possibilities. As a matter of fact, the figures have two, three, and four lines of symmetry, respectively, and some are neither horizontal nor vertical:

I don’t know how much this text teaches about rotation symmetries. A figure with n-fold rotation symmetry, if it also has any line (reflection) symmetries, will have n lines of symmetry, as you can see above: the figures have twofold, threefold, and fourfold rotation symmetries, respectively, and have corresponding numbers of lines of symmetry.

There is plenty more that one could observe here; we’re in the realm of “point groups in two dimensions”, a topic of abstract algebra, important in chemistry. I’ll just point out one more thing: any figure with n-fold rotation symmetry, where n is even, has point symmetry (symmetry under reflection in a point). As noted in your text, point symmetry is the same as 180° (or twofold) rotation symmetry. A figure with n-fold rotation symmetry, where n is composite, also has m-fold symmetry for any m that divides n — such as 2, in the case of figure (C).

As far as I can see, the book doesn’t go beyond defining symmetries. These are just hints that there is much more to learn about all this!

Jim replied:

Thank you for that additional information. All of your replies I have printed and keep in the text I’m reading for future reference.

Yes, I was aware that in question #17 is it only the lack of point symmetry that rules out figure B. I went ahead and mentioned its lack of horizontal symmetry anyway just to show that I knew about it.

Thanks again.

Composite transformations … notation, and multiple answers

A few days later, we moved on to a harder composition question:

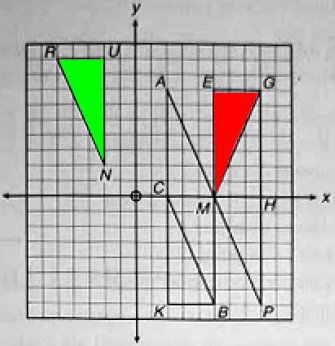

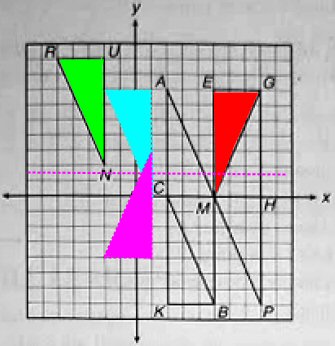

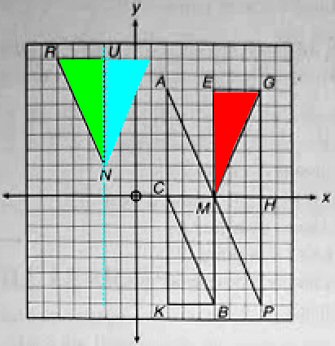

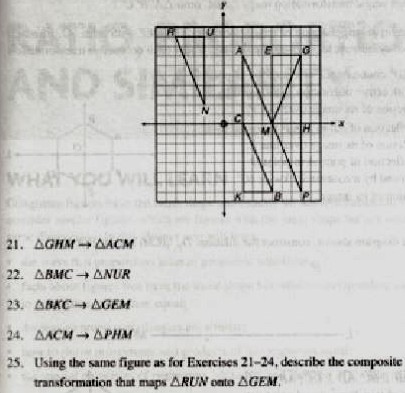

Question #25 says to “describe the composite transformation that maps triangle RUN to triangle GEM.”

On the coordinate grid, the coordinates for RUN are R(-5, 9), U(-2, 9), N (-2, 2). The coordinates of GEM are G(8, 7), E(5, 7), M(5, 0).

To answer the question I would first do a reflection of RUN over the y-axis, thereby making the coordinates of R’U’N’ thus: R’(5, 9), U’(2, 9), N’(2, 2). Next I would do a translation of 3 units horizontally, -2 units vertically: T(3, -2).

The answer the book gives for question #25, if not clear in the attached image, is this:

T3, -2 and r y=1.5

I understand the T3,-2 as the translation (though I don’t know why that would come first). It’s the “ry=1.5” I don’t understand. The lowercase “r” would stand for “reflection,” and the “y” for the y-axis, but where does the “1.5” come from?

Looking in the book now, I see that the notation is clearly defined; Jim hadn’t shown us what they say about it. We’ll look at that later.

I answered:

Hi, Jim.

First, presumably ry=1.5 means the reflection over the line y = 1.5, which is horizontal, rather than over the y axis. But it looks like a misprint, because that would have the wrong effect. They appear to have meant rx=3.

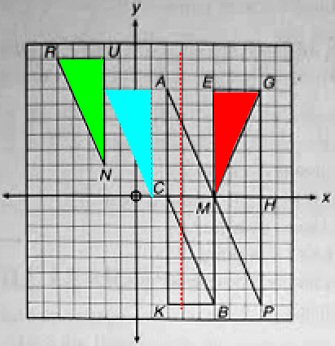

But there are many different ways to obtain a given composite transformation, so presumably they gave only one possible answer. They chose to do a translation first, then a reflection, and they made a rather odd choice.

My first thought was that they might want you to use one of the triangles shown as the intermediate figure, but T3,-2 takes RUN to points that are not shown at all. Here is the actual result of T3,-2 followed by ry=1.5:

The result is the purple triangle, not the intended red one!

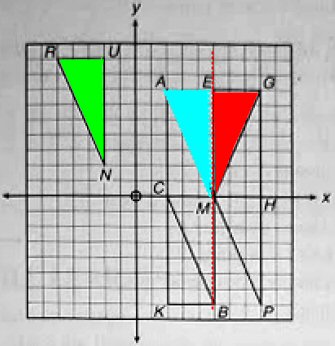

Here is T3,-2 followed by rx=3, which may be what they intended:

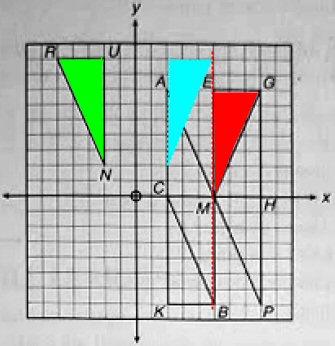

If I wanted to translate first as they did, I might have done this (T7,-2 followed by rx=5):

But I might also do T-3,-2 followed by rx=0. (Too hard to show!)

If I wanted to reflect first, I might have used the y-axis (rx=0) followed by T3,-2, which is just what you suggest:

Or I could have done rx=-2 followed by T7,-2.

And so on!

So I’m not really sure what they intended, but I certainly hope they have said that there are many correct answers.

Can I see their answers for the other problems? Also, perhaps, an example of how they notate a composite transformation.

It is common for students to think they are wrong when the book shows a different answer than theirs; they really should tell you (at least once per chapter) when there are problems you can solve different ways!

In editing this, I notice that #25 could have been described as a single transformation: a glide reflection with line \(x=1.5\) and translation \(T_{0,-2}\)!

Jim replied:

Hi Dr. Peterson,

Thank you for your quick and helpful reply. I had not considered the many ways you mentioned to map triangle RUN onto triangle GEM. I just latched on to the first way that came to mind and went with it. Unfortunately, I don’t recall the book ever saying, “there are many ways of solving problem x; here we give one way of solving it.”

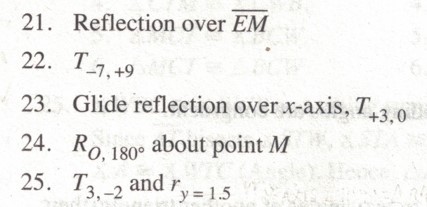

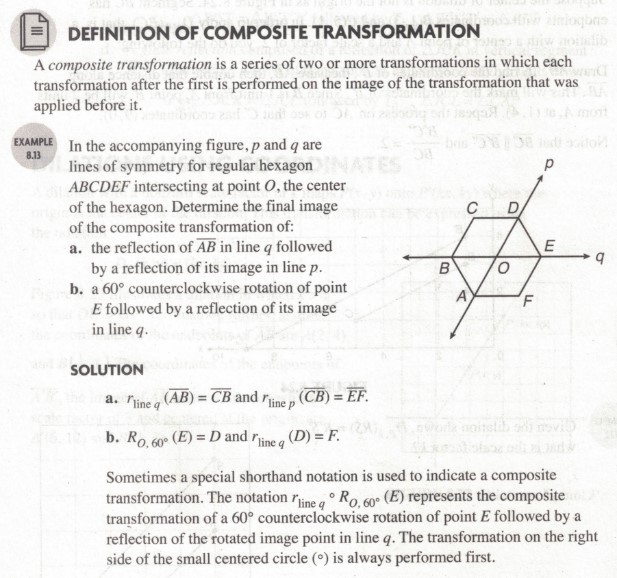

Attached are the requested answers to the other problems listed in my earlier attachment “Question-25-b,” as well as an example of how they notate a composite transformation.

Thanks again.

The provided answers include a mish-mash of different styles, including one error we’ve seen before. The example of a composite transformation uses line names in the notation for reflection, because they can’t use equations here.

I responded:

Thanks.

One thing I was interested in was to see if they had used the same notation for reflections before the answer you asked about; but they didn’t.

The answer to #21 ought to be rx=5 if they used the notation rather than words. They don’t seem to have a single notation for glide reflection for #23; I don’t know if there is a common notation at this level. And for #24, I don’t know what the O means; I expected RM,180°, to represent rotation about M. It looks as if they forgot that the notation shown would mean rotation about the origin only.

I don’t get a very good impression of this book!

As I said above, I was only seeing the errors in the book; the rest is much better!

Now that I have the book, I can see all of their notation, which they state clearly even though they don’t use it consistently. Here is what they say on a summary page (184), giving formulas:

- Line reflection:

- \(r_{y-axis}(x,y)=(-x,y)\)

- \(r_{x-axis}(x,y)=(x,-y)\)

- \(r_{origin}(x,y)=(-x,-y)\)

- \(r_{y=x}(x,y)=(y,x)\)

- \(r_{y=-x}(x,y)=(-y,-x)\)

- Rotation:

- \(R_{O,90^\circ}(x,y)=(-y,x)\)

- \(R_{O,180^\circ}(x,y)=(-x,-y)\)

- \(R_{O,270^\circ}(x,y)=(y,-x)\)

- Translation:

- \(T_{h,k}(x,y)=(x+h,y+k)\)

- Dilation:

- \(D_{origin,k}(x,y)=(kx,ky)\)

Not knowing that, I found some online sources that give largely the same notation, and sent those links. One doesn’t mention the center in their rotation notation, but just assumed the origin (which is reasonable, given that nobody gives a formula applicable to any point). None gave a notation for glide reflection apart from representing it as a composition.

One thing to notice, though, is that formulas for reflection over general lines, or rotation by other angles, are beyond the scope of these sources, so although the book uses the notation for these, they are not included in the formula list.

Jim replied:

Hi Dr. Peterson,

Thank you for your comments about the notation and the helpful links. Yes, the book I’m studying doesn’t seem to have consistent notation. Often there is a mix of notation and verbal description. You wrote, “The answer to #21 ought to be rx=5 if they used the notation rather than words.” That makes sense, and I don’t think the book ever uses that type of reflection notation. You also wrote, “And for #24, I don’t know what the O means; I expected RM,180°, to represent rotation about M.” The book’s glossary defines “origin” as “the zero point on a number line,” yet sometimes that “O” is put in notation when something else is meant.

I’ve finished the chapter on “Geometry Transformation” and have started the chapter “Ratio, Proportion, and Similarity,” which, so far, looks more promising. Since I’m about halfway through the book I’d like to finish it. The Math Doctors website says, “We accept any kind of question about any kind of math, from any kind of person,” so I hope that includes stubborn persons like me.

I responded:

You may notice some stubbornness (or obsessiveness) in me, too. Happy to help.