Last time we looked at what it means to translate, rotate, and reflect figures on a plane. Here, we’ll look at some questions about what happens when these three transformations (and a fourth, the glide reflection) are combined.

Composition of two transformations

Recall that the transformations we call translation (slide), rotation (turn), and reflection (flip) are all isometries, meaning movements that do not change the shape, which means that all measurements (“metry”) remain the same (“iso”).

This question from 1997 asks about combining two of them, which is where they start to become interesting:

Product of Isometries I am currently enrolled in an enriched Euclidean geometry class. In a recent assignment, I was asked to use the three isometries (translation, rotation, and reflection) in composition with each other and deduce the net result of the two transformations. For example, I worked out that the product of a reflection followed by a reflection through a line parallel to the first line results in a net translation. However, if the lines intersect, the net result is a rotation. The major problem occurs when I consider a translation followed by a rotation. My teacher claims that there is a fixed point around which the image may be rotated to obtain the net result. I'm having difficulty convincing myself of this, as I can't find a point which results in the same image. Any help would be appreciated, including referral to other sources of information on the Web, etc.

Composition of transformations is the same as compositions of functions: Do one after the other, and the result is a new transformation. We’ll see that any composition of any two in the list of four types of transformations results in one of the same four types, which may or may not surprise you.

Two reflections

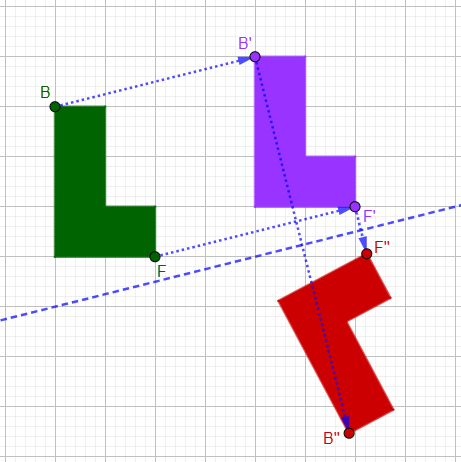

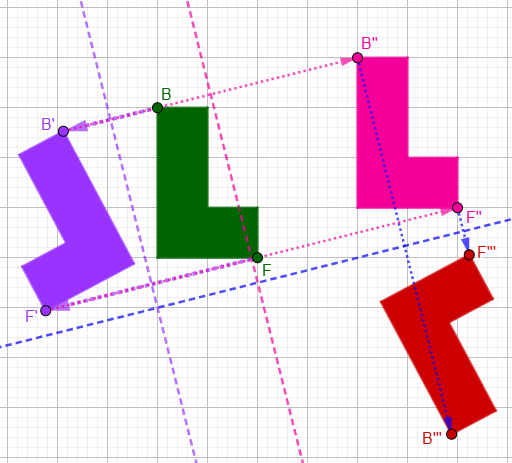

First, let’s fill you in on the part Marie had already worked out! Here are examples of the two cases of combining two reflections:

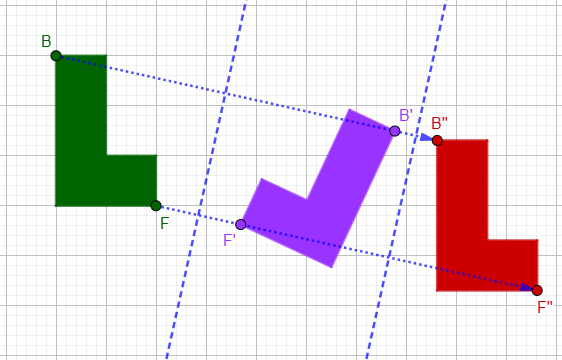

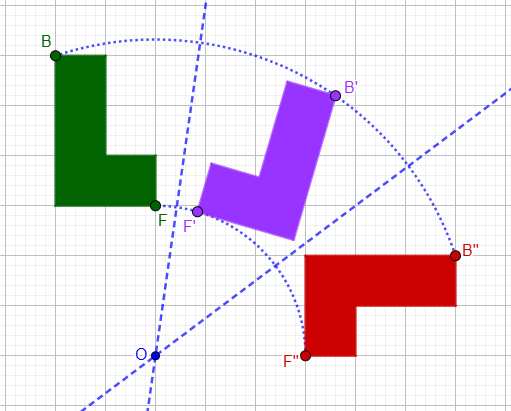

Reflections across two parallel lines:

This results in a translation by twice the distance between the lines. You can see why, by considering how each reflection moves point B.

Reflections across two intersecting lines:

This results in a rotation about the intersection of the lines, by twice the angle between the lines. Again, look at how each reflection moves point B, relative to the intersection point O, which becomes the center of rotation.

The last question last time related closely to this fact, because there an explicit reflection, followed by a reflection across the T’s line of symmetry, yielded a rotation:

Translation and rotation

I actually showed last time that what looks at first like a translation followed by a rotation can actually be accomplished by a single rotation around a different center. Here, we’ll see how and why it works.

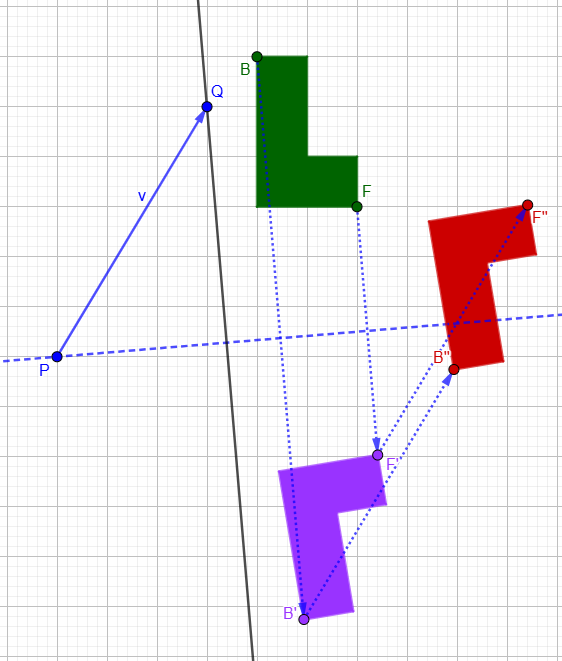

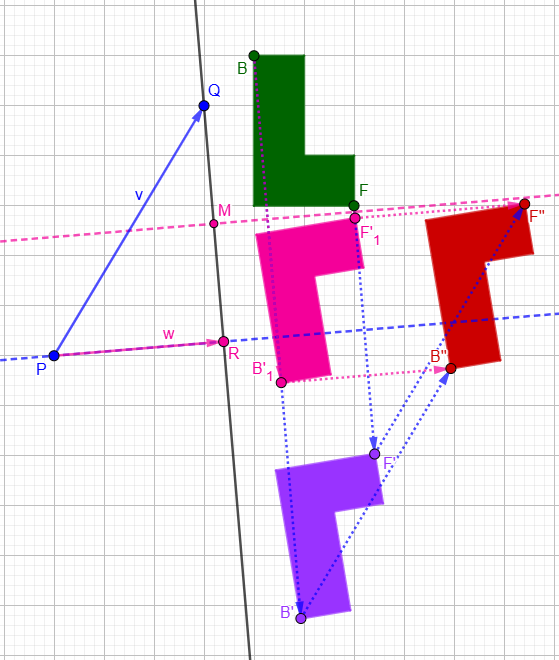

To repeat, we are given a translation followed by a rotation, and want to find a single rotation that does the same thing:

Doctor Tom answered:

Hi Marie, Here's how I think about it. It's hard to draw a picture using only typing, so I suggest you draw a picture as you try to follow what I'm saying. The rotation occurs about some point, right? Call that point P. The translation moved some point that was previously at Q to that point P. On your paper, make two points and label them Q and P. Draw an arrow from Q to P to represent the translation. Every other point in the plane moved parallel to that arrow and by exactly the same amount. Now draw a circle around P that has a larger diameter than the arrow from Q to P. If you imagine sliding that arrow parallel to itself until it touches the circle at two points, then if the rotation is opposite the direction of the arrow and by an angle such that the arrow touches the circle at two points that are exactly that angle apart, you will have found a point that is moved back to itself. The translation takes it along the arrow that you moved to touch the circle in 2 places, and then the rotation undoes it. If the rotation is in the opposite direction, slide the arrow to the opposite side of the circle and you'll get the same result.

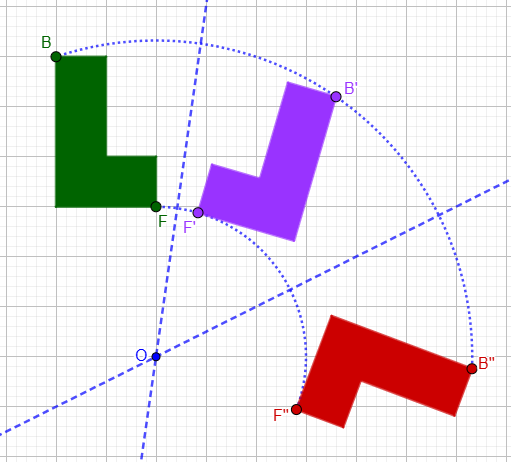

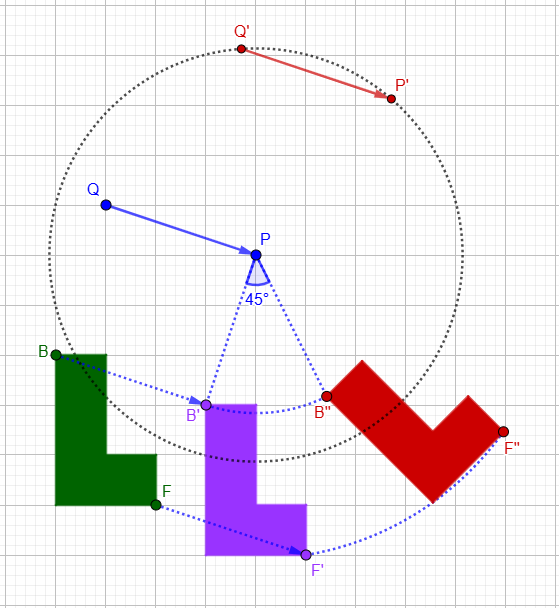

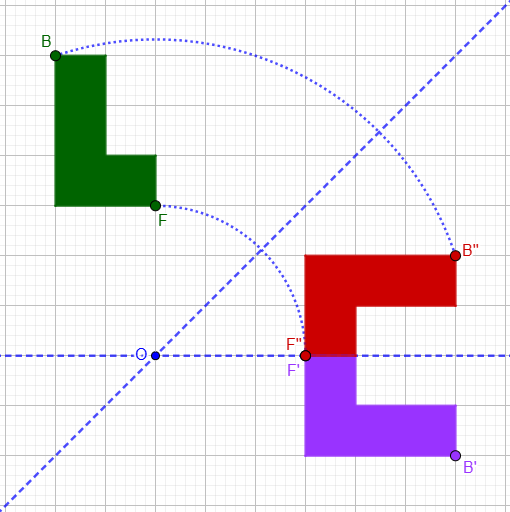

Here’s the picture, based on the example above:

The idea here is that the original composite transformation translates Q’ to P’ and then rotates around P taking P’ back to Q’, so it leaves Q’ unchanged; this can then be the center of a rotation.

But of course this won't work if the angle is wrong. But the size of the circle can be anything. What you need to do is pick a radius for that circle that is exactly large enough that the length of the arrow connecting 2 points on the circumference of the circle describes a sector of the circle that has exactly the angle of rotation. I've been a little sloppy here, but you can calculate the size of the circle exactly, and from there determine exactly which point is fixed. I hope this is enough of a hint to get you going!

What he’s saying is that we want angle P’PQ’ (which is the same as angle QQ’P) to be the same as our original angle of rotation. I did, in fact, do everything right here, as we can see:

The important thing is that that can always be done; in effect, we are constructing isosceles triangle QQ’P with the correct apex angle.

(I actually constructed my drawing by constructing perpendicular bisectors of BB” and FF”, with the center of rotation Q’ at their intersection. I could do that because I knew that the resulting transformation would be a rotation.)

When you learn either some linear algebra or topology, this problem will seem trivial. When I saw the problem, I instantly found 2 proofs - one involving "eigenvalues" of the transformation matrix, and one invoking Brower's fixed-point theorem on a mapping of projective space, but that wasn't going to help you much. It actually took about 5 minutes of work for me to convert those "instant" proofs into something that was purely geometric. Tell your teacher it's a good problem.

We can do something similar with any composition of two isometries, such as a reflection and a rotation.

Decomposing any transformation into reflections

We can also do the opposite: Given one transformation, find a series of reflections that are equivalent.

Consider this question from 2005:

Transformations in the 2D Plane as Composition of Reflections I am teaching Geometry--reflection, rotation, transformations--and this is not my area of knowledge. (It is a summer school objective, not one I regularly teach.) Considering the 4 symmetry transformations--reflection, rotation, translations, and glide reflections, is it possible to express any transformation as a composition of at most three reflections?

We haven’t yet talked about glide reflection, which is included here as the fourth kind of isometry. That is just a translation combined with a reflection in a line parallel to the motion; the only reason it has a name of its own is so that any isometry (including the result of combining two) has a name of its own. We’ll see it below.

And “symmetry transformation” is another name for “isometry”. We’ll see why when we examine symmetry.

Doctor Douglas answered:

Hi, Michelle. This sounds like the "geometric transformations" of a 2D plane (at least the ones that preserve scale--no magnification/shrinking is involved). Yes, every plane motion is the composition of three or fewer reflections. Let me give you some questions and activities that you can work on with your students to help think about why that is the case:

We’ll look at how to obtain each of the isometries in turn, in the form of an exploration with students.

Reflection = 1 or 3 reflections

A reflection is of course a composition of one reflection --itself. It can also be a composition of three reflections, but not two (ask your students: why not?) It may help to investigate what a series of N reflections does to say a capital letter "R"

It may sound odd to talk about “a composition of one reflection”! But mathematicians have no trouble talking about, say, a sum that may have only one term.

Why must it be an odd number of reflections? Because each reflection changes orientation, so an even number of them would not change orientation, and couldn’t be a reflection! (I’ve been using L for the same purpose as the R suggested here, namely demonstrating with an asymmetrical shape to make sure changes of orientation are visible.)

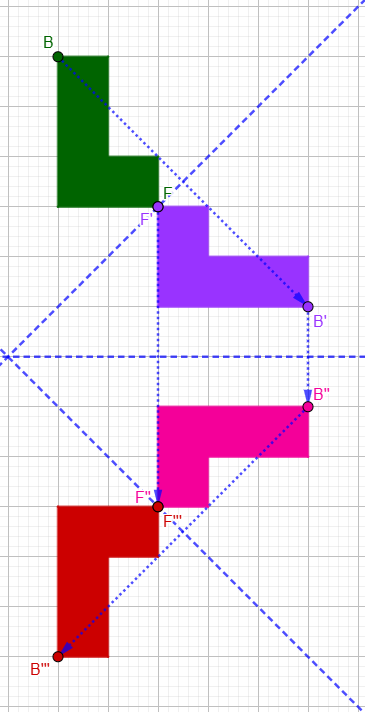

We could obviously use three parallel reflections (or even three across the same line!) But they don’t have to be:

Here the net effect is a reflection across the horizontal line.

Now, if we just make any series of three reflections, the result will not in general be a single reflection. Rather, as we saw above, two reflections may combine to make either a translation or a rotation, so three will make either a glide reflection (see the last question below!) or a rotation. To make a single reflection, we need to make a “glideless glide reflection” by canceling any slide that might develop. In the example above, I had to get the rotated second image in the right place for the final reflection.

Rotation = two reflections

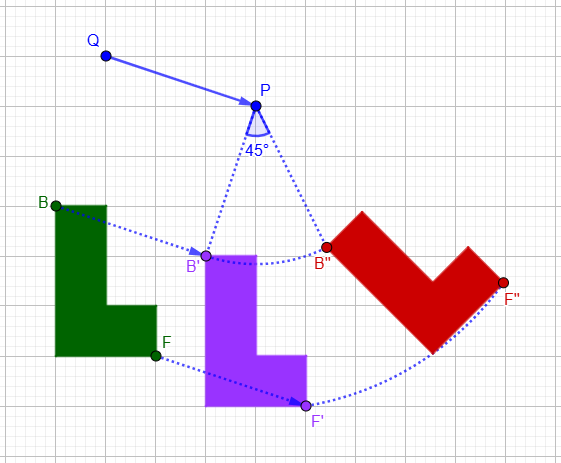

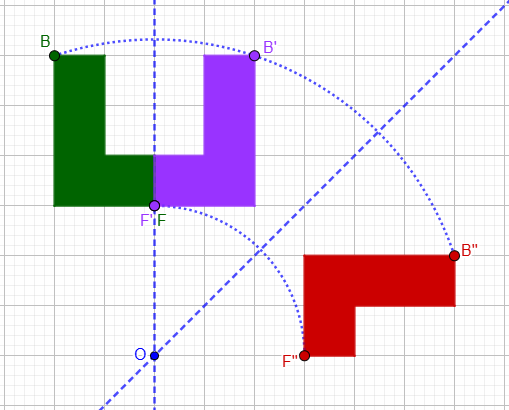

Any rotation is the combination of two reflections. You might guess that it is two because of the way it transforms the letter "R". Can your students find two reflections that work? Where do the reflection axes intersect and what is the measure of the angle between them?

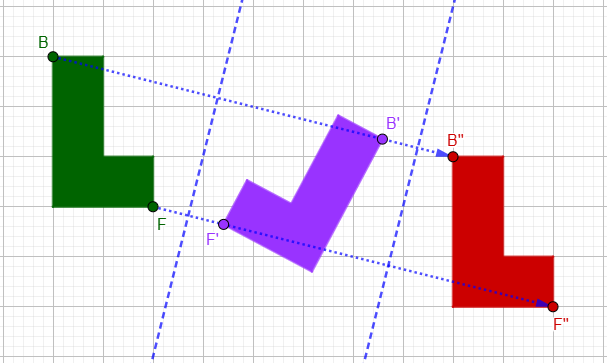

We saw this above, observing that we can draw two lines that intersect at the center of rotation, at half the angle of rotation. For 90° rotation about O, for example, we can draw two lines at a 45° degree angle through O, like this:

Any pair of such lines will work, like this:

Or even this, where the second reflection is “backward”:

This is an important feature of this problem: The solution is not unique, even when only two steps are allowed.

Translation = two reflections

A translation is a composition of two reflections. Ask your students: "Why not one and why not three?" Again, it may help to imagine a capital letter "R". A further topic is to ask your students to see if they can IDENTIFY or CONSTRUCT two reflections that combine to make any given translation (for example "6 meters northwest"). If they are comfortable with the Cartesian coordinate plane this will be easier, but it can be done just by drawing reflection axes. This type of thinking is good geometric training. Is the set of two reflections unique or is there more than one possible set that works? For the set(s) that do work, do you notice anything curious about the directions of the reflection axes, relative to each other and relative to the translation direction? Can you relate the distance between the reflection axes and the distance of the translation?

There are too many good questions here for me to explore them all; but I can show some of the results I got from playing with GeoGebra to “discover” how it all works; if students can be provided such tools, they can be a wonderful addition to this discussion. There are also sets of mirrors that can be used to experiment in a more tactile way.

Since we saw above that parallel reflections result in a translation by twice the distance between them, we can just use two lines perpendicular to the translation, and the right distance apart:

But those two lines can be wherever we want:

Glide reflection = three reflections

Any glide reflection is of course a combination of a translation with a reflection, so if you can make a translation with two reflections, then you can make a glide reflection with three reflections. Can your students exhibit three reflections that work?

Here is a glide reflection:

Now we just have to replace the translation with two parallel reflections, perpendicular to the line we already have:

(Here I chose to reflect first to the left, and then to the right.)

But in the last question below, we’ll see that we can combine translation and reflection in different directions, and still obtain a glide reflection. So with some creativity, we could do it with three reflections that are all in different directions.

There's still more work to be done to fully establish that any plane transformation that preserves scale is the composition of at most three reflections. For example, you would have to prove that the combination of a translation with a rotation is a (different) rotation.

Ultimately, what he suggests proving is that any combination of the isometries of the four types is an isometry of one of those same types – that is, the four types are all there are. It seems likely that this has already been proved in this course, so that the question is complete as asked. But this is why, as I said, we bother to name glide reflections!

What if a glide isn’t parallel to the reflection?

We’ll close with a creative question about those glide reflections, from 1998:

Non-parallel Glide Reflections I am in training to be a future teacher. We received some questions that were asked by high school students, and we are supposed to answer them. A lot of them I can answer but this one really stumped me. Can you help me? "If a glide reflection is defined to be the composition of a line reflection and a translation (or glide) in a direction parallel to the axis of reflection, what is the composition when the translation is not parallel to the axis of reflection?" I'll thank you in advance for any help you may be able to give me on this.

Another way to ask this would be, What isometry results when you combine a translation and a reflection that are not parallel?

I answered:

Hi, Stacy. I was a little confused by this myself, because glide reflections are always defined this way, so it's a good question what happens if you relax the definition. But then I experimented a little (using the Geometer's Sketchpad) and found that in fact if you translate by any vector the result is still a glide reflection! I probably should have known this, but discovering it was fun and an experience that I would recommend sharing with a student.

This is a nice kind of question to ask when you meet a definition; as we often say, the best thing to do when you are faced with a “what if it were otherwise” question is to try it. (We did something similar recently with the definition of complex numbers.)

So I tried it:

If I reflect object 1 in line L (2) and translate by vector V (3):

| 3

+--

_*

/|

/

V/ | 2

/ +--

/ L

+-----------------------------------------

+--

| 1

the result is the same as if I reflected it in line M parallel to L, which is the perpendicular bisector of segment QR, and translated it by vector PR parallel to L:

| 2 | 3

+-- +--

_+Q

/|

/ | M

- -V/ -|- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

/ |

/ | L

+---->+-----------------------------------

P R

+--

| 1

The original translation PQ is replaced by the sum of PR (the parallel glide) and RQ (in the direction of the motion caused by the reflection). We need to move the mirror half that far to correct for it.

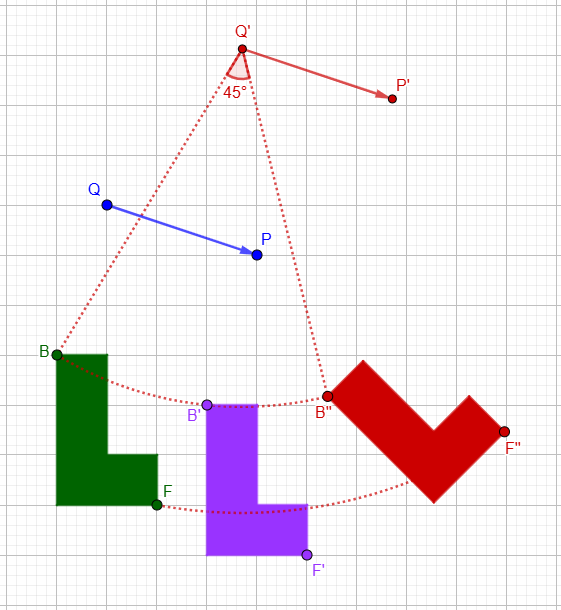

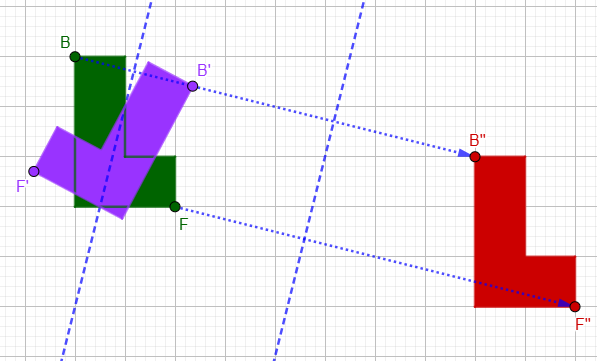

Here’s a real example (using GeoGebra, the current equivalent to Geometer’s Sketchpad). First, the translation and reflection:

Now, the equivalent glide reflection:

The vector w = PR is the projection of the original vector v = PQ on the line of reflection; M is the midpoint of QR.

If we did the translation first, we would do the same thing, except the new line of reflection would be on the other side.

So we define glide reflection as we do, only for convenience. It allows us to have a unique description of any glide reflection defined by a single directed line segment PR. If I were talking to the student who asked the question, I would ask the class to experiment with this without revealing the outcome, so they could discover it themselves; then perhaps they could try to prove it.