Last time I started a series looking at the Order of Operations from various perspectives. This time I want to consider several kinds of misunderstandings we often see.

Multiplication before division?

Here is a question from 2005 from a teacher, “WRW”:

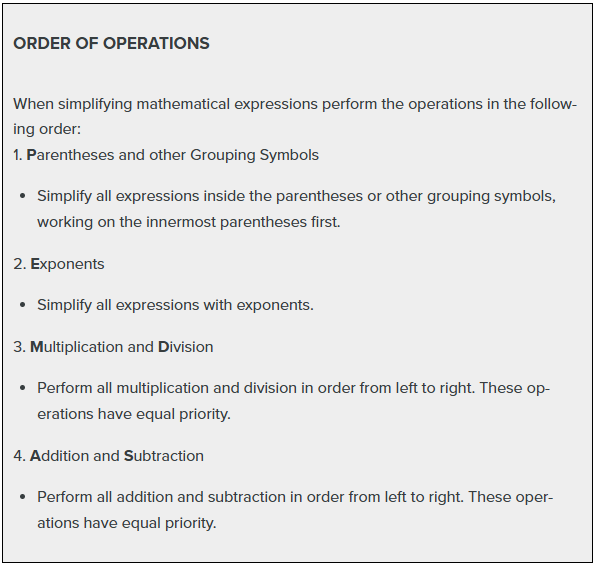

Confusion over Interpretation of PEMDAS In telling students to "do multiplication and division IN THE ORDER THEY APPEAR," it seems they want to always do multiplication first. I think they follow the PEMDAS rule BY THE LETTER, so they want to multiply before dividing. When doing multiplication first, 8 / 2 * 4 = 8 / 8 = 1 When doing multiplication and division from left to right, 8 / 2 * 4 = 4 * 4 = 16

I agreed with him:

If you think that students have a tendency to misinterpret the rule, you're probably right; but I think the reason is that PEMDAS is a poorly stated version of the rule, and it is easy to misunderstand it as meaning you do Multiplication, then Division, then Addition, then Subtraction. That's not what the rule is supposed to mean, but many students don't get past the letters and see the meaning! It's really wiser to think of subtraction as addition of the opposite, and division as multiplication by the reciprocal, and just leave D and S out of PEMDAS entirely, rather than try to fit them into the rules. But we make the rules for people who aren't ready to see things in a mathematically mature way! (I myself prefer to avoid PEMDAS altogether, and teach the "rules" in a more natural way that leads into this mature perspective.)

Where some people memorize the rule as “Please Excuse My Dear Aunt Sally”, if I use a mnemonic at all, I make it PEMA: “Please Excuse My Attitude”. It’s just Exponent-stuff, Multiplication-stuff, and Addition-stuff, with Parentheses acting as traffic cop, telling you when to do something other than what the signs say. I’ll include my own way of introducing the concept in a later post on why we need the rules.

But, continuing with an example:

Translating these ideas into the case of multiplication and division, when we write

8 / 2 * 4

we really mean

8 * 1/2 * 4

which we can do in any order, since multiplication is commutative; clearly, however you do it, it comes out to 16, not 1. The problem here is that people tend to see this as if it said

8

-----

2 * 4

which means something different.

Note particularly that if we did the multiplication first in my example, then instead of $$8\times\frac{1}{2}\times 4 = 16,$$ we would be doing $$8\times\frac{1}{2\times 4} = 1.$$ Interpreting it correctly, the only number we divide by is the 2.

Also, seeing it this way allows me to rearrange the expression at will (since multiplication, unlike division, is associative and commutative). If I had, for example, $$7 \div 3\times 15,$$ I could think of it as $$7 \times \frac{1}{3}\times 15 = 7 \times 15 \times \frac{1}{3} =7 \times \left(15 \div 3\right) = 7\times 5 = 35$$ In effect, I’m dragging the division sign around with the number following it!

“WRW” answered,

Thanks so much! I really like the idea of thinking of division as multiplying by the reciprocal and turning the whole multiplication/division portion into just multiplication. I'll try that out with my students and see if it helps. Thanks again!

I didn’t mention there the fact that students outside of America are taught mnemonics like BODMAS, and students there sometimes think Division has to be done before Multiplication. Get them together, and you might have quite an argument!

Addition before subtraction?

Here’s a question from another teacher, Monica, the next year:

Incorrect Application of PEMDAS and Order of Operations I was working with students on the order of operations today and explained that multiplication and division are done from left to right, as are addition and subtraction. Apparently, they believe they were taught in the past to do all addition and then all subtraction. I tried to show examples of why that wouldn't work, but they simply did the problem their way, obtained a different answer and asked why it was incorrect. Are there any examples or explanations that would clearly explain why they must be done from left to right?

The same reasoning I gave for multiplication applies here, as I explained:

It's impossible to show that they MUST be done from left to right; that is nothing more than a convention we all agree on. Your class has shown that it makes a difference which order you use; that proves that we MUST make some choice that we can all follow. What that choice is, is not so definite. But it makes a lot of sense to go left to right, for the following reason.

You can’t prove that a particular grammar is “correct”, as if nature forced us to use it; every language has a different grammar, and each is correct for its own speakers. What makes a grammar correct is only that it is the same grammar used by other speakers of the language. So you’d have to prove that addition and subtraction are done left to right by showing that all the books do it that way.

But we can see why it was a good idea. It’s the same thing I said about multiplication and division:

We define subtraction this way: a - b = a + -b This allows us to think of any subtraction as an addition; we essentially just attach the negative sign to the number following it, rather than taking it as a different operation. The subtraction requires no extra rules, just the rules we already have for addition. If we do this, then 2 - 3 + 4 = 2 + -3 + 4 = 3 That is the same result we get if we do the operations from left to right (and it doesn't depend on whether we do the ADDITIONS from left to right, since addition is commutative!). If we did the addition first, we would get 2 - 3 + 4 = 2 - (3 + 4) = 2 + -(3 + 4) = 2 + -7 = -5 Note that this time, the negative sign ended up applying to ALL the following numbers, rather than just to the one after it.

So doing additions first would mean we are really subtracting everything after a subtraction sign. One benefit of replacing subtraction with addition of a negative, as in the multiplication case above, is to be able to move things around. For example, a common trick to evaluate a string of additions and subtractions more easily is to move all the subtractions to the end: $$5 + 3\ -\ 6 + 2\ -\ 8 + 1 = 5 + 3 + 2 + 1\ -\ 6\ -\ 8 = (5 + 3 + 2 + 1)\ -\ (6 + 8) = 11 – 14 = -3.$$ Without left-to-right operations, we couldn’t do this; we would have to look at the whole expression before rewriting any one subtraction as addition of the negative.

So doing additions and subtractions from left to right makes it easier to transform an expression into one involving only addition; and since addition is commutative and associative, it is MUCH nicer to work with! The rule, therefore, arises from the wish to make expressions easier to handle. Without it, a lot of algebra would turn out to be a lot harder. So your students should thank whoever first made this choice!

I closed by referring to the MD question above:

Now, your student's misunderstanding of the rule very likely comes from the use of PEMDAS or something equivalent, which is meant to be only a summary of the rules. It sounds as if A comes before S, but that twists the intended meaning of the mnemonic. See this page for another thought:

Confusion over Interpretation of PEMDAS

http://mathforum.org/library/drmath/view/66614.html

That says essentially the same thing I just said, but about multiplication and division, which is an even bigger problem. (Did you know that in other countries they use BODMAS instead of PEMDAS, so students often think division should be done first?)

For another interesting take on left-to-right operations, see

Left Associativity

Where do negatives fit in?

One of the most common difficulties in evaluating expressions is the mixing of negation with exponents. We have had many questions on this; in fact, I could have included this in the series Frequently Questioned Answers. I’ve chosen to use this question from 2002, whose answer covers most of the ideas we bring up (and refers to several other answers):

Negative Squared, or Squared Negative? After reading your answer in Exponents and Negative numbers http://mathforum.org/library/drmath/view/55709.html it seems to me that you're ignoring an important fact: -3 isn't just -1*3, but a number in its own right, i.e., the number 3 units to the left of zero. If that's the case, then shouldn't -3^2 have the value -3*-3, or 9? If -3 was intended to mean -1*3, then shouldn't it be written that way and not implied? Thank you for your time.

The answer he referred to is an early one from 1997 where Doctor Ken stated that \(-3^2 = -9\), because it means \(-(3^2)\), not \((-3)^2\). Now, if the convention is that negation is done after exponentiation, then that’s all we need to say. But Tom is arguing from the fact that \(-3\) is itself a number, so it has to be kept together. Does that require us to do the negation first? He has a strong argument (and a common one).

I took the question:

I do recognize that it is possible to disagree on -3^2. Dr. Rick's answer to a similar question, Squaring Negative Numbers http://mathforum.org/library/drmath/view/55713.html mentions this disagreement. Like you, he notes that if you think of -3 as a single number, it makes sense for the negation to bind more tightly to the 3 than any operation. That reasoning makes some sense, though I think other arguments are stronger. But I do agree that since there _is_ some reason to read it either way, it is prudent always to include parentheses one way or the other, to clarify your intent, i.e., to write either -(3^2) or (-3)^2.

Minimally, we can say that it is wisest to avoid this form, either because it is easy to read wrongly, or because all the books teach it wrong (depending on your opinion)! In fact, I find that the books I most respect never show such a form (making it hard to find examples to point to!), while others, on the contrary, emphasize it because students always get it wrong unless it is drilled into them.

Occasionally people will try to argue the point based on the behaviors of particular calculators or spreadsheet programs. However, these are really irrelevant, since they all define their own input formats, and programmers (of which I am one) are notorious for choosing what's easiest for them, rather than what is most appropriate for the user. I've noted in several answers in our archives that some calculators, and Excel, use non-standard orders of operation without apology. But calculators in particular just don't use standard algebraic notation in the first place.

I’ll be including a link to one of these discussions at the bottom. But the main point is simply that calculators have to follow a convention that suits the way you enter expressions on them, which is different from print. (As calculators have come to display expressions more like type, however, they have been forced to follow conventions more closely.)

We also get questions from people who claim they learned long ago something different from what their children or grandchildren are learning (either the whole PEMDAS business, or some part of it like this one):

There also seems to be a generational difference, with older people (including some teachers) claiming that they were taught to interpret -3^2 as (-3)^2. I suspect that what has changed is not the rules governing "order of operation" (operation precedence), but that schools are introducing the issue earlier, before students get into algebra proper. That means that they start by looking at expressions for which it is less clear why the rules make sense. I think you will rarely find examples of "-3^2" in practice, because there is no need for mathematicians to write it. You will find "-x^2" frequently.

Conventions of algebra apply primarily where we have variables; in arithmetic you don’t normally write long expressions with numbers, but just evaluate as you go. Basic four-function calculators were designed for such use, and don’t follow the order of operations. And the conventions make more sense on their home turf (with variables than with numbers):

If you approach the idea starting with numerical expressions like -3^2, you are thinking of -3 as a number and assuming that the expression says to square it. If you approach it first using variables, having first discovered that "-" in a negative number is actually an operator, then it is easier to see why -x^2 should be taken as the negative of the square. So I'll start with the latter, and then it becomes natural to treat numbers the same way we treat variables.

The point here is that in arithmetic, we see the negative sign as part of the number (“the number I’m attached to is negative”); in algebra, we see it primarily as an operator (“negate the thing that follows”). And the convention arises in the latter context. It isn’t primarily meant for use with numbers, but with variables.

Negation as multiplication or addition

Now, in an expression like -x, clearly "-" is a (unary) operator, which takes a value "x" and converts it to its opposite, or negative. The expression "-x" is not just a single symbol, but a statement that something is to be done to a value. As soon as we start combining symbols like this, as in -x^2 or -x*y, we have to decide what order to use in evaluating them. The trouble is that the "order of operations" rules as commonly taught (PEMDAS) don't mention negatives. So if we are going to go by the rules, we have to figure out how a negative relates to them. Well, there are two ways to express a negative in terms of binary operations.

There is no N in PEMDAS, or even in many fuller explanations of the convention. To see where it fits, we need to think about how its meaning relates to the other operations. How do mathematicians think of negation?

One is as multiplication by -1:

-x = -1 * x

Treating it this way, clearly

-x^2 = -1 * x^2 = -(x^2)

That is, since -x means a product, we have to do the exponentiation first.

So if we think of negation as a kind of multiplication, it belongs right in there with MD. And, if you think about it, you’ll realize it doesn’t matter whether we think of it as being done first, last, or left-to-right: If you negate a factor before multiplying or dividing, you get the same answer as if you negate after multiplying or dividing:

$$(-x)\cdot y = -(x\cdot y)$$

The other way to talk about negation is as the additive inverse, subtracting x from 0:

-x = 0 - x

(This is why the "-" sign is used for both negation and subtraction.) Using this view, we see that

-x^2 = 0 - x^2 = -(x^2)

In particular, we would like to be able to replace subtraction with negation wherever we find it, and not mess things up: \(x\ -\ y^2 = x + -y^2\), which would not be true if the latter meant \(x + (-y)^2\). This is why the subtraction idea is applicable even when we are not actually subtracting from 0.

So both views of negation produce the same interpretation, which does exponents first, and it is logical to put negation here in the order of precedence.

So if PEMDAS really means PE(MD)(AS), with operations in parentheses being done together, we can extend it as PE(NMD)(AS), where negation is definitely done after exponents and before addition.

But the fact is that there is no authority decreeing these rules; just as in the grammar of English, we get the "rules" by observing how the language is actually used, not by deducing them from some first principles. The order of operations is just the grammar of algebra. So the real question is, how do mathematicians really interpret negatives and exponents combined in an expression?

If you look in books, you will rarely find "-3^2" written out, but you will often find polynomials with negative coefficients. And you will find that

-x^2 + 3x - 2

is read as the negative of the square of x, plus three times x, minus 2.

So, even though there is not a lot of evidence of usage with numbers, usage in polynomials (with variables) is clearly on the side of negation-after-exponentiation, and we want to be consistent.

I have come to believe that the order of operations is what it is largely so that polynomials can be written efficiently. If "-x^2" meant the square of -x, then we would have to write this as

-(x^2) + 3x - 2

to make it mean what we intend. Since powers are the core of a polynomial, we ensure that powers are evaluated first, followed by products and negatives (the two ways to write a coefficient) and then sums (adding the terms).

Since we can easily see that this is how -x^2 is universally interpreted, it makes sense to treat -3^2 the same way.

Addition comes last so that a polynomial is a sum of terms; negation goes with multiplication in order to have the same base in every term, without having to use parentheses to avoid accidentally changing a base to \(-x\).

For some other discussions of this issue that haven’t already been mentioned, see

Precedence of Unary Operators Negative Numbers Combined with Exponentials Negative vs. Subtraction in Order of Operations

And for a long discussion with a programmer, see

Order of Operations and Negation in Excel

That is the discussion I referred to above, about how calculators and programs have different needs, as well as whether -3 should be thought of as a unitary entity.

Pingback: Order of Operations: Subtle Distinctions – The Math Doctors

My mathematically minded friend told me that when there are no brackets you complete the equation left to right. If there are brackets you use BEDMAS. Is this true?

No. In fact, “BEDMAS” is mostly about what to do in the absence of brackets (parentheses)! The role of brackets is just to intentionally change the order of evaluation from the default, which is multiplication and divisions before addition and subtraction. And if we used brackets everywhere, we wouldn’t need the “EDMAS” part at all.

See the previous post, Order of Operations: The Basics.

I am discussing this expression on a Facebook group:

8÷2(2+2) = ?

My answer is 16. My opponent says 1.

She insists that the multiplication must be done first, because it has a special connection with the parentheses.

Who is right?

Hi, Helge.

You’re both wrong … to be arguing over this. The fact is that different conventions are taught about this sort of expression, so each of you would be right according to some teachers. (For which reason, it’s best never to write such an expression, if you want to be understood.)

For details, see the post Order of Operations: Implicit Multiplication?, and its follow-up, Order of Operations: Historical Caveats.

If you have further questions about this, you should ask us directly, via Ask a Question.

Pingback: Why Properties Matter: Beyond Addition and Multiplication – The Math Doctors

Full disclosure, I’m a PEMDAS fanatic. (Promoting PEMDAS to the level of “1+1=2”, and there can be only one correct answer or answer set.) Amen. I would, without any crisis of faith, accept BODMAS as the one true rule. Processing mixed operations left to right ignores the fact that not all cultures process their written information that way.

Near the beginning of this page, an equation was rewritten by substituting “/ 2” with “* 1/2” resulting in an equation where the commutative property of multiplication can be used. That substitution requires a huge assumption: The operation 2 * 4 could not be performed before the 8 / 2. [Otherwise, the rewritten equation would be “8 * (1 /(2 * 4))” which essentially makes the commutative property of multiplication a moot point.] The example actually highlights the importance of operator order in rewriting equations for manipulation. An inaccurate substitution condemns any further manipulations to produce errant results.

Hi, David.

I’m not quite sure what you mean by “PEMDAS”, and therefore what interpretation you are defending or refuting. You seem to think multiplications and divisions should not be done from left to right; but that is what we mean by PEMDAS, as I explained here, and also in Order of Operations: The Basics. If you are taking PEMDAS to mean “Multiplication, then Division”, why do you also approve of BODMAS, which in the same way would be taken to mean “Division, then Multiplication”? That is not what they mean; they mean what I described here.

This post explains why we choose to define the order of operations in this way. This is a choice; it is not based on any particular culture, or on an assumption that all cultures read left to right.

You’re right that we need to take the meaning of an expression into account when we make a substitution, and not mechanically replace one set of characters with another. That is the cause of several common errors.

But what we did here is not an error. The assumption I am making is that mathematicians do read expressions this way, which you can easily confirm.

Sorry to reopen the question about -3^2, but I was arguing about this on YouTube, and many people seem to be convinced that as a standalone expression it should be considered as 9, while others say it must be ambiguous, because there is not an universally accepted answer.

The point is that many calculators give 9 as the result, including the one in Excel. It is also the answer in many scientific calculators, but that is because they don’t let an expression to start with the binary minus but only with the unary one, that for them has more precedence than the rest of operations. Therefore, typing -3^2 ends meaning 9.

I read your previous post that what calculators say shouldn’t be considered the rules of what we do on paper, and also that it is hard to find examples of expressions like -3^2 in math texts, because when we write something like it is because we were dealing with variables.

But my question is: since the actual appearances of standalone expressions like -3^2 end occurring mostly when typing in calculators, not in math texts, can we teach that the actual answer for it must be -9 despite that is not what people will find in “practice”? Or at least not always in practice, as the answer tends to differ: in Google and WolframAlpha, it means -9.

I have also put as an argument that a standalone expression as -3^2 can come from a more complex one, and thinking about it as 9 can lead to some problems. For example, if we are solving this equation:

5 – 3^2 = 5 + F(x)

no one doubts that the left side means 5 – (3^2).

But we realize we can subtract 5 in both sides, leaving:

-3^2 = F(x)

If we were to interpret -3^2 as (-3)^2 when it appears alone, we would need to add here new parentheses to keep the original meaning, add a factor (-1), or be forced to write a zero:

-(3)^2 = F(x)

(-1) * 3^2 = F(x)

0 – 3^2 = F(x)

because otherwise we would have no longer an equivalent equation to the original. Instead, if our convention is that -3^2 is always interpreted as -(3^2) regardless of the context, then we can just remove the redundant term 5 without the need of modifying the structure of the rest because of that.

I don’t know if the argument is wrong or some people didn’t understand the implied problem, but they insist that if the expression didn’t reflect a subtraction from the beginning, the minus sign should be part of the number.

Hi, Ronald.

I think your arguments in favor of taking -3^2 to mean -9 agree with ours. (I hope you do see that we are saying it is -9, not 9.)

We simply have to recognize that there are many people who don’t see things the way mathematicians do, and therefore we should “write defensively” and avoid that form. There’s no need (for either them or us) to argue about it. They can merely be told that, however irrational they think it is, it is the convention among mathematicians that -3^2 = -9. In exactly the same way, we who know that convention can recognize that, however irrational we know it is that Excel says -3^2 = 9, that is their convention and we have to live with it.

As for calculators, I think (most?) scientific calculators distinguish the “-” (subtract) button from the “(-)” (negate) button, though they could probably use one button, just as computer languages typically use one symbol. My guess is that they do this in part so that they can distinguish between starting an expression with a negation, and continuing a previous result by subtracting from it. But they typically give both subtraction and negation a lower precedence than exponentiation. That has not always been true, and it is not true in Excel (which is stuck with their rule for the sake of backward compatibility). Which calculators do you find give the answer as 9?

I find the link at the end, Order of Operations and Negation in Excel, a particularly interesting read.

Hello.

For sure, I was aware that the article intended that it is -9 and not 9.

I was just going to type that my CASIO fx-82MS scientific calculator returned 9 when using negation, and to my suprise, when I tested it, the result was indeed -9. Maybe it was a Mandela Effect? Maybe I took that word from someone else and assumed it to be true, since we usually don’t have the need to write expressions like that, so I wasn’t used to knowing what to expect from the calculator. Despite this, I could not ensure that all versions of a scientific CASIO give the same result.

In the YouTube video in which I was arguing this, someone mentioned that in some old math texts they interpreted expressions like -3^2 as -3 * -3, but didn’t give references. I suspect it was a Mandela Effect too.

I think that finding that the results in software programs are most of the time the same as those agreed upon in mathematics is an additional argument to say that the interpretation to learn should definitely be one and not the other, and Excel should be taught as a separate case to be careful with.

And thanks for sharing that article, which I found interesting! Seriously, before finding that YouTube video, I didn’t suspect there was much debate about it.

Yes, I think it is appropriate to explicitly teach that -3^2 = -9 in written mathematics, even though some software or calculators may not interpret it that way, and some humans may not as well. The former fits most usage they will see (including, I think, most current calculators), while the latter is a warning to be careful in reading what others write, and in writing for others.

And, yes, the reason that calculators and the like seem to tend in the direction of agreeing with what teachers say is because … that’s what teachers say! They want to be right, and to be recommended by teachers.

I feel like this is a fundamental problem of our notation using the minus sign for multiple operations.

What do you take of the case of a negative exponent? If we follow the negation-after-exponentiation example proposed then a^-b becomes a much different equation than convention dictates. Most would assume a^-b is a^(-b) as written, but if we follow negation-after-exponentiation it would be a^-1*b.

So negation in a base should conventionally be after exponentiation, but negation in a exponent should be conventionally before exponentiation. That to me sounds like a poor/ambiguous convention.

This is a very interesting question, which I don’t think I’ve ever heard before. It raises several issues that are worth addressing.

First, I has to be noted that in traditional formatting, the question you raise is moot, because when written as \(a^{-b}\), the entire exponent is written as a superscript, which inherently groups it; you have to evaluate the entire exponent before using it. As a result, when this is written in in-line format using the “^” (caret) symbol, you would write it as “a^(-b)” in order to express that grouping. Either way, there is never a question as to which operation is done first.

Second, restricting ourselves to the latter format, I claim that it is unambiguous to write \(a^{-b}\) as a^-b, because there is still only one way to interpret it, regardless of the order of operations. That is because the caret says to use the immediately following number as an exponent, and since “-” itself is not a number, we can only take all of “-b” as the exponent. As a unary operation, “-” acts only on the number on its right, so in this position, it is not “in competition” with exponentiation in the order of operations.

Third, your argument, as I understand it, is based on what I said about “-x^2 = -1 * x^2 = -(x^2)”, where I replaced negation with multiplication by -1. But you can’t just replace an expression anywhere with an expression that would be equivalent when standing alone, without first considering the order of operations. (I discussed this idea in this more recent post, under “Substitution requires it”.) To do your substitution, you would properly write, not “a^-1*b”, but “a^(-1*b)”, because of my second point (that “-b” must be treated as a unit, so that parentheses are appropriate to maintain that). Also, note that if you instead used my “-x^2 = 0 – x^2 = -(x^2)” as a model, you would get “a^-b = a^0 – b = 1 – b”. This further illustrates the error of blind substitution.

(My two statements are not presented as proofs that the negation on the left is done after the exponentiation, but as two experiments to see what makes most sense; it is their agreement that provides support for the choice to do exponents (on the left) before negation. As I just showed, attempting the same experiment with negation of the exponent shows that that leads to inconsistency.)

Fourth, if the rule as stated results in an interpretation different from the very convention that the rule is supposed to state, then clearly we need to change our statement of the rule, not the convention! If you were right that “negation after exponentiation” would entail taking a^-b as (a^-1)b, and we know very well that it is taken as a^(-b), then we would want to change our wording, not its meaning. I think that’s what you are saying.

In summary, I’m not sure whether your point is that we simply shouldn’t use “-” for negation (an idea discussed here), or that the convention has to be stated in your longer form in two parts (which I think unnecessary because of my second point), or something else. I think what we have is perfectly consistent.

Pingback: Order of Operations: Fractions, Evaluating, and Simplifying – The Math Doctors

On the negative numbers: One expression I use to try to confound the Facebook OOO crowd is the following:

6 ÷ -(1 + 2)

Is it 6 ÷ -3 or -6 * 3?

Surprisingly, those who think 6 ÷ 2(1 + 2) = 9 would say that that the answer to my problem is -2! I was taught that a negative sign in front of parentheses without a coefficient is the same as multiplying what is inside the parentheses by -1, so I would have guessed they’d say -18. I believe the answer should be -2, however, just like I believe 6 ÷ 2(1 + 2) = 1.

Hi, Scott.

I don’t see why anyone would say that 6 ÷ -(1 + 2) = -18. The only way to get that is to blindly replace -(1+2) with -1*(1+2), ignoring how it would change the order of operations in the surrounding expression. I discussed such unthinking substitutions (in a very similar context) in Implied Multiplication 3: You Can’t Prove It. But there is no reason anyone would do that here, because it is already clear what to do.

As I said above in response to Andrew, “you can’t just replace an expression anywhere with an expression that would be equivalent when standing alone, without first considering the order of operations.”

By the way, looking at your site, I find numerous places where I would disagree with you; but I see no value in arguing about this or “trying to confound” people who disagree with me. My goal is peace and mutual understanding, not proving myself correct. Acknowledging ambiguity (even merely potential ambiguity) is a central part of that.

Dave,

Near the top of the page, you stated

“Translating these ideas into the case of multiplication and division, when we write

8 / 2 * 4

we really mean

8 * 1/2 * 4

which we can do in any order, since multiplication is commutative; clearly, however you do it, it comes out to 16, not 1. The problem here is that people tend to see this as if it said

8

—–

2 * 4

which means something different.”

It doesn’t mean something different, and

your reciprocal calculation is wrong. Not ambiguous. Just wrong.

TERMS are reciprocated. Not factors.

So your reciprocal will be

1

———

2*4

————

Expression Reciprocal

1

2x ——

2x

———————————————-

3 x

—— ——

x 3

———————————————

2x-3 (x+5)

———- ———-

(x+5) 2x-3

Reciprocal in Algebra

https://mathsisfun.com/algebra/reciprocal.html

—————

Reciprocals.

Which of the following is the reciprocal of

21 × 5?

1

Correct answer is: ———-

21×5

https://www.splashlearn.com/math-vocabulary/reciprocal

————-

The proof of 1/(ab) = (1/a)*(1/b)

consists in showing that, (1/a)*(1/b)

acts as the reciprocal of ab, and

the product of ab*(1/a)*(1/(b) = 1

Mary Dolciani

Teachers Manual

Page 17 Book 1

Modern Algebra

Structure and Method

Doug,

I’m sorry, but as in your previous comments, this is simply wrong.

You are assuming, contrary to convention, that all multiplications are done before any divisions. Some authors have taught that, but even the sources you quote here teach otherwise:

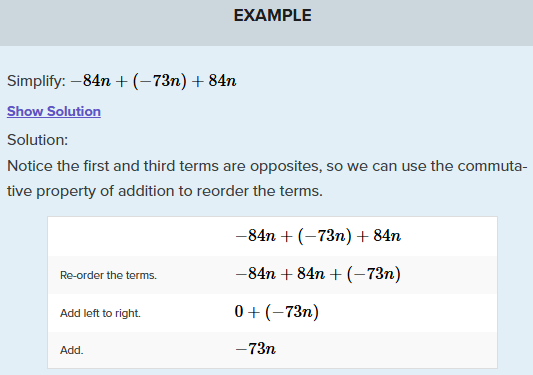

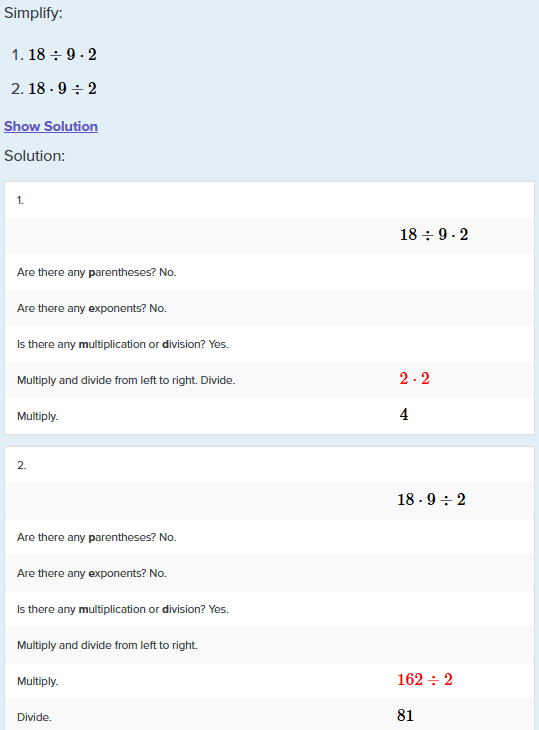

MathsIsFun says, “Divide and Multiply rank equally (and go left to right),” and gives the example

Similarly, SplashLearn says, “Multiplication and Division: Next, moving from left to right, multiply and/or divide, whichever comes first,” and gives the example

Dolciani also teaches left-to-right, at least for explicit multiplication. (In some books, she taught that implicit multiplication is done first, but that is not relevant here.) I showed that in my previous response.

As a result of this misunderstanding, you seem to assume that “/” means “take the reciprocal of the product that follows”, which it does not; your examples of reciprocals don’t deal with the symbolic form in which you are claiming to prove me wrong, but only with words; so they are irrelevant. The fact that the reciprocal of \(21\times5\) is \(\frac{1}{21\times5}\) does not imply that 1/21 × 5 means the reciprocal of 21 × 5. Rather, it means “the reciprocal of 21, times 5”, or \(\frac{1}{21}\times5\).

[I tried to edit your comment to insert images of what you quoted; here they are:

]

I hope this is clear.

Hi Dave,

I’m not assuming every multiplication should be done first however, for these expressions, the multiplications do come first.

For instance 2b÷2b= 1, NOT b²

Now 21*5÷21*5 = 1 and 1*21*5=21*5

Now taking the reciprocal of 21*5 which is 1/(21*5)

which you already have the example, gives

1/(21*5)*21*5= 1

Now previously , you questioned my use of the Commutative Law, ab=ba.

8÷2*4=8÷4*2 can only equal 1

Commutative Law states, factors can be presented in any order, without changing the result of the expression.

Now this Law contradicts the convention that is PEMDAS. Do we use a convention, or do we use

an actual Mathematical Law.

You are promoting PEMDAS as the ONLY way to simplify expressions, and that is most definitely NOT the case.

I’ll stick with the Laws of Maths.

Regards

Doug

Thanks for condensing your argument, so I can answer it more easily. I hope this time you will understand what I have been saying.

Let’s take a look at what you quoted, from an online textbook:

(First, let me point out that, like last time, you included a link only to the publisher of the snippet you quoted; I had to search to locate it specifically, which will make it easier to answer, by seeing the context, so I edited your comment to improve the link.)

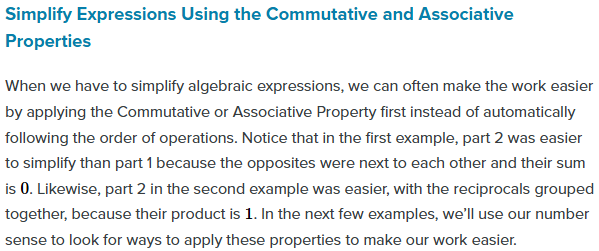

What they are saying here is not that you should apply properties instead of following the order of operations, as if these would give different results. They are saying that, whereas the order of operations tells you what an expression means, you don’t have to evaluate the expression in that order, but can apply properties to simplify the work. In the example, they observe that two of the terms cancel one another, so it is easier to add them first, rather than to do everything left to right. The order of operations rules tell you that it means “this, plus this, plus this”, but the commutative property tells you that you will get the same result if you change the order. Other examples on that page show the same concept.

Now, you say that you aren’t claiming that all multiplications are done before divisions, but that in these examples, they are. Yet the only grounds you give for that claim is that, as you see them, the multiplication are done first. On that assumption, you then apply the commutative property to that product. But the standard rules (as taught by Lumen as well as the others I’ve pointed out), \(21\times5\div21\times5\) does not mean \((21\times5)\div(21\times5)=1\), but \(((21\times5)\div21)\times5=25\).

Here is what they teach:

If you were right, the first example would equal 1, not 4. But they follow the order of operations – the same rules they mention in the section on simplifying, and do not violate; they just rewrite the expression before evaluating.

Similarly, all current textbooks I know (though not all, historically) would say that \(8\div2\times4\) means \((8\div2)\times4=16\), while \(8\div4\times2\) means \((8\div4)\times2=4\).

And, again, the commutative property must be applied to the correct meaning of the expression, according to those rules, and does not override the rules. If two factors are not meant to be multiplied together, then you can’t change their order. A law can’t contradict a convention! The latter takes precedence, and determines when the law can be applied.

Doug,

If you want to continue debating this, please don’t just keep repeating the same claims; rather, try to understand and answer my arguments. In particular, explain why every source you quote agrees with me that an expression like 18÷9×2 means (18÷9)×2, not 18÷(9×2), as you take it. Are you the only person in the world who understands mathematics correctly? Or is there some chance that you might be wrong? The reality is that the order of operations convention does have to be applied first, in order to know what an expression is intended to mean, before you can correctly apply properties to rewrite it.

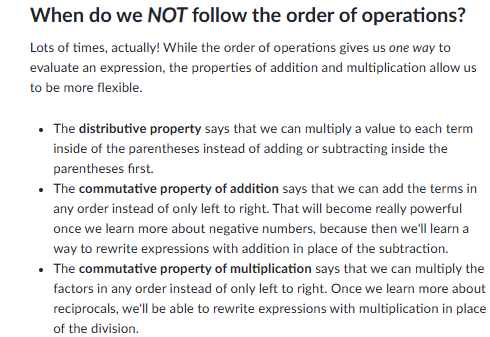

Then why does Khan Academy show the following-

Khan Academy.

When do we NOT follow the order of operations?

Lots of times, actually! While the order of operations gives us one way to evaluate an expression, the properties of addition and multiplication allow us to be more flexible.

* The distributive property says that we can multiply a value to each term inside of the parentheses instead of adding or subtracting inside the parentheses first.

* The commutative property of multiplication says that we can multiply the factors in any order instead of only left to right. Once we learn more about reciprocals, we’ll be able to rewrite expressions with multiplication in place of the division.

The order of operations, or the convention of performing arithmetic calculations in a certain sequence, is not a universal or natural law, but a human invention that developed over time and across cultures.

https://www.khanacademy.org

Exponents and order of operations FAQ (article) | Khan Academy

The answer is the same as what I explained before.

You are quoting from here in Khan Academy:

By “not following”, they don’t mean “disregarding” the convention, disobeying it, but rather going beyond it: recognizing, once we understand the meaning of an expression (according to the order of operations), we can use properties as a tool to change how we choose to carry out the work of evaluating it.

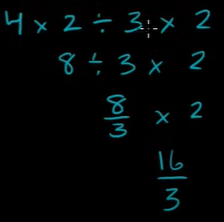

As I’ve shown for your other sources, Khan, too, disagrees with you about expressions of the sort you are interested in. For example, at the end of the video here, he does this:

He does not do the \(3\times2\) first, but does everything from left to right.

I have not often seen students confused in this way by the term “order of operations”, though I can see how it can happen. It doesn’t mean “you must always do the operations in this order”, but just “what is written means that it could be done in this order, but you can rewrite it, if you want, before you do all the operations”. That’s what this site, and the book you used last time, are saying.

Once students have learned the basics, I usually explain that they have a choice between doing “exactly what an expression says” (which is what the order of operations indicates), and “whatever is the easiest way to evaluate it” (which the properties allow you to do). Some even get in the habit of automatically distributing, even when that actually makes the work harder; others never get beyond taking an expression literally. You, on the other hand, seem to be unaware of your own misinterpretation, because somehow doing multiplication first feels so natural to you that you aren’t even aware that you are interpreting at all, much less that you are doing so wrongly.

Again: Before you can apply the commutative property, you must determine what numbers are to be multiplied. That is what the order of operations does: It says, before you do this addition, for example, you will have to multiply these numbers. Once you understand what the expression means, then you can decide to rewrite it as an equivalent expression (with the same value) by rearranging parts of it, if you wish. But that doesn’t mean that you can swap any numbers that are separated by a multiplication sign without first considering whether those numbers are to be multiplied.

A different example may help. We also have the commutative property of addition. But when I see the expression \(2\times5+4\times3\), I can’t swap the 5 and 4 to get \(2\times4+5\times3\); that gives a different value, because the 5 and 4 are not meant to be added. We have to see that they have to be multiplied by the 2 and the 3, respectively, before we do the addition. So the numbers actually being added are \(2\times5\) and \(4\times3\); if we were to apply the commutative property of addition, we would actually get \(4\times3+2\times5\).

In the examples we have been discussing, like \(8\div2\times4\), the numbers you claim can be commuted are not meant to be multiplied! And we know that because the order of operations tells us that, nominally, the division will be done before the multiplication. Yes, we can rewrite it if we want, but that might be as \(8\times4\div2\), or just as \(\frac{8}{2}\times4\).

Hi Dave

Thank you for the prompt reply,

So from the above 8/2*4

Does it follow that ab÷ab = b²

Regards,

Doug

Ah! That’s the $64,000 question! I thought you’d never get around to it. But it’s a separate issue.

You’ve been talking about explicit multiplication. where there is hardly any question (but see here, and other references here to what I call “AMF”).

When you take out the multiplication sign, you get to the issue of implicit multiplication, which people fight over. Since there are different opinions, and it can be easily misread even if you have a strong opinion, I recommend just never writing expressions like ab÷ab.

I think there is a very good case for treating that as (ab)÷(ab) = 1. But some teachers, at least, insist on treating it the same as a×b÷a×b = ((a×b)÷a)×b = b², and there is some reason to believe that replacing one notation for multiplication with another should not change the meaning of an expression.

But that’s the subject of several other pages on this site, starting with Order of Operations: Implicit Multiplication?. In fact, you’ve previously commented on a more recent page on that topic, though you used explicit multiplication, making your comment irrelevant there.