Some time ago we looked at the meaning of the definition of limits, and I included several links to additional discussions on the subject. Now I want to took at three of those, which fit together rather nicely. We’ll look deeply into the proof that the limit of \(x^2\), as x approaches 2, is 4, as three Math Doctors contribute their ideas.

What was the author thinking?

First, recall the definition of a limit (as stated in Epsilons, Deltas, and Limits — Oh, My!):

We say that \(\displaystyle\lim_{x\rightarrow a}f(x)=L\) when, for any positive number \(\epsilon\), there exists a positive number \(\delta\) such that for any \(x\ne a\) such that \(\left|x-a\right|<\delta\), the function value will satisfy \(\left|f(x)-L\right|<\epsilon\).

We’ll be looking at three discussions of the proof that \(\displaystyle\lim_{x\rightarrow 2}x^2=4\). The textbook by Larson, Hostetler, and Edwards gives this proof as an example:

You must show that for each \(\epsilon>0\), there exists a \(\delta>0\) such that

$$|x^2-4|<\epsilon\text{ whenever }0<|x-2|<\delta.$$

To find an appropriate \(\delta\), begin by writing \(|x^2-4|=|x-2||x+2|\). For all x in the interval \((1,3)\), you know that \(|x+2|<5\). So, letting \(\delta\) be the minimum of \(\epsilon/5\) and 1, it follows that, whenever \(0<|x-2|<\delta\), you have

$$|x^2-4|=|x-2||x+2|<\left(\frac{\epsilon}{5}\right)(5)=\epsilon.$$

Clear? Probably not, if this is new to you! We’ll be creeping up on a full understanding as we go.

Here is a 1999 question asking us to work through the details of essentially the same proof:

Epsilon/Delta Definition of Limits I'm an older student trying to regain some lost ground in calculus. At this point in my course I'm having difficulty grasping the full concept of the epsilon/delta definition of limits. Graphically it makes complete sense. However, when you describe the same problem in numerical terms, some of it falls apart (for me, anyway.) For example: Find the limit x^2 = 4 as x -> 2 Solving using epsilon/delta limits: |x^2-4| < epsilon whenever 0 < |x-2| < delta [Everything looks okay up to this point.] Factored terms: |x-2||x+2| < epsilon [This also seems to make sense, but now the text example seems to go into la-la land.] For all x in the interval (1,3) [Where did this interval come from? No mention of bounds was made until this point in the problem. No help to be found in previous examples either. Is this step supposed to be intuitive?] * the example continues: we know that |x+2| < 5 [I guess they found the epsilon value by plugging in the upper bound of x into f(x)-L. I hate math books that don't leave at least a couple of bread crumbs to follow.] * finally the text solution: letting delta be a minimum of (epsilon/5) and 1. [Epsilon/5 and 1?] it follows that whenever 0 < |x-2| < epsilon/5 we have |x^2-4| = |x-2||x+2| < (epsilon/5)*5 = epsilon [How did they get epsilon/5?]

Proofs like this are too often shown without (a) showing how the author would have chosen to do what he did, and (b) making the overall logic clear. That will be the goal of this post.

Filling in some gaps

Doctor Jerry answered first:

I suppose the author was thinking something like this: We want to make |x-2||x+2| small. We can control the |x-2| with the delta. That leaves |x+2|. Somehow we must control its size. So, if we begin by deciding that x is within 1 of its limit of 2, that makes x between 1 and 3. This is arbitrary. One could say, let's require x to be between 0 and 5. But 1 on either side of the limit 2 is natural. So, to begin with, we make delta less than 1. If this much is true, then x is in the interval (1,3) and so: |x-2||x+2| < |x-2|*5 Now all that remains is to put a SECOND requirement on delta. We want it so that: |x-2||x+2| < |x-2|*5 < delta*5 < epsilon So, we choose delta to be the smaller of 1 and epsilon/5, so that both steps in our procedure hold.

So, where did the interval \((1,3)\) come from? It was chosen (arbitrarily) in order to keep the second factor under control, so we could make the product as small as we need to. Since we have control over \(\delta\), and we expect it to be small anyway, we can promise ourselves that it won’t be greater than 1.

And where did \(\epsilon/5\) come from? That’s what delta needs to be in order that multiplying it by 5 won’t take the product over epsilon.

So by taking the smaller of 1 and \(\epsilon/5\), we can make the function value as close to 4 as needed.

If that’s not enough of an answer, we’ll be seeing more as we proceed.

Thinking about the overall process

Two days later, Doctor Hans joined in:

Thanks for writing to Dr. Math. Let me try to add a few comments to your example.

You want to show that lim{x->2} x^2 = 4, or in the epsilon-delta terminology:

For all EPSILON > 0 there exists a DELTA > 0 so that the following is true:

If you choose x so that |x-2| < DELTA then you will have |x^2-4| < EPSILON.

So, in other words, given EPSILON > 0, your 'job' is to find DELTA > 0 so that if you choose any number x in the interval (2-DELTA, 2+DELTA), then this number will satisfy |x^2-4| < EPSILON.

Once we find a suitable delta, we need to show that the function value will be appropriately close to 4 when x is that close to 2. The actual proof will be the showing. The finding is what I call the exploration step.

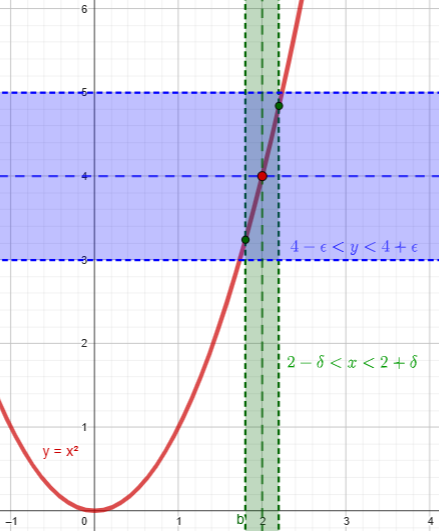

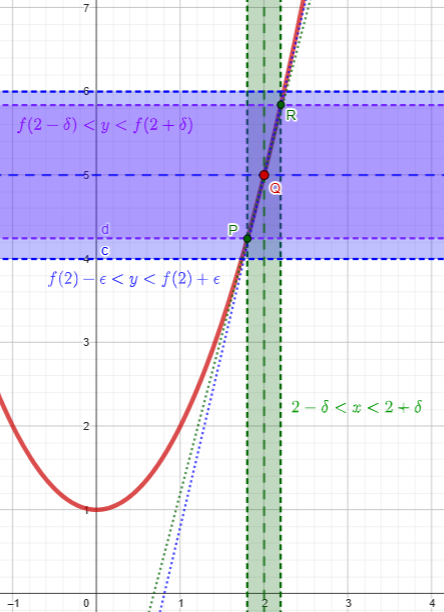

Here, for example, I have taken epsilon (\(\epsilon\)) as 1, and found a delta (\(\delta\)), namely 0.2, such that y will be within the blue region as long as x is in the green region:

A proof has to show that we can always do this. (Note that I just chose some value for \(\delta\) that works; I could have used a smaller, or slightly larger, value. What I chose is the \(\epsilon/5\) of the proof.)

In the example we will choose DELTA <= 1. Hence the interval (1,3). There is nothing special about the number 1 in this case; it is just to make our 'search' easier. We choose a smaller set in which to look for our DELTA.

|x+2| < 5

This is obvious when we have decided only to look at x in (1, 3).

|x-2| < DELTA

This is true when we choose x in (2-DELTA, 2+DELTA).

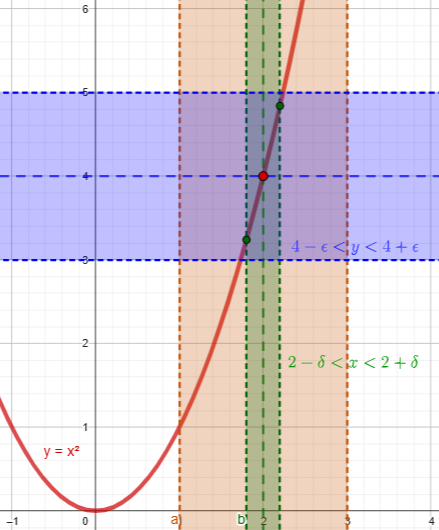

As Doctor Jerry said, the choice of 1 is arbitrary. Suppose we had chosen to require delta to be no more than 2, rather than 1. Then we would know that x is in \((2-2,2+2)=(0,4)\), so that \(|x+2|<4+2=6\) rather than 5.

Note that (2-DELTA, 2+DELTA) is contained in (1, 3), so if we choose x in (2-DELTA, 2+DELTA) we get, by the above:

|x^2-4| = |x-2||x+2| < DELTA*5

If we choose DELTA so that DELTA*5 < EPSILON then we will have |x^2-4| < EPSILON (and we will be done).

But that is easy: choose DELTA < EPSILON/5. That is the reason why EPSILON/5 is chosen.

If we’d chosen 2 rather than 1, as above, then we would want \(\displaystyle\delta<\frac{\epsilon}{6}\) (as well as \(\delta<2\)), so we’d use the minimum of those.

Here I have restricted delta to the interval from 1 to 3 (orange); and I took delta to be \(\delta=\frac{\epsilon}{5}=0.2\):

Here. I restricted delta only to the interval from 0 to 4, and took delta to be \(\displaystyle\delta=\frac{\epsilon}{6}=0.166…\):

This makes delta even smaller, because we have less control over \(x+2\).

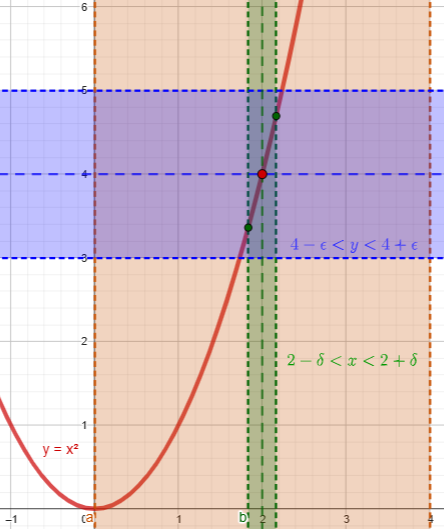

But if we restrict x even more, taking \(\delta<0.1\), then the calculated delta is larger than that, namely \(\displaystyle\delta=\frac{\epsilon}{4.1}\approx0.244\); and the restriction comes into play, forcing us to use \(\delta=0.1\) instead:

Here the calculated delta (green) is too wide, but using the maximum of 0.1 (orange) works.

The choice can be even more arbitrary!

Out next question is from 2002, with a broader question about an equivalent limit:

Delta-Epsilon Proofs and Arbitrary Epsilon Choice Dear Doctor Math, The limit of f(x)=x^2 + 1 as x approaches 2 is 5. Now a rigorous proof of this would seem to involve showing that for any choice of epsilon, the corresponding value for delta is min{1, epsilon/5}. Just what is this rigorous proof? How is delta = epsilon/5 obtained? More generally, what is the nature of the special relationship between a function's behavior near a point, the choice of epsilon, and a corresponding "good" delta? I hope that this is not too much to ask.

Note that this problem is equivalent to the other; if \(\displaystyle\lim_{x\rightarrow 2}x^2=4\), then \(\displaystyle\lim_{x\rightarrow 2}x^2+1=5\), and vice versa. The entire proof is identical, once we’ve written \(|(x^2+1)-5|=|x^2-4|<\epsilon\).

I answered:

Hi, Morris. There are actually many ways you can choose delta; the choice of 1 in your answer is arbitrary, and any delta less than what you show will be satisfactory. There is no need to find the "best" delta, only one that will guarantee that the resulting error will be less than epsilon. In fact, there are entirely different ways to choose delta for this example, as you'll see in the second link below. I think a general answer to your general question is that the bounds on the slope of the function in the neighborhood of the point under consideration will play a large role in determining what delta will look like.

The key here is that we only have to find some value of delta that will work (and then prove that it does); even once we find one, any value less than that will still work!

I then gave links to four previous answers: the one we saw above, and one that was used in each post of the 2018 series of three. The “second link”, in particular, is “A Limit Proof Using Estimation” in A Closer Look at a Limit Proof. That is very much worth reading, as it is about the very same limit we are discussing here, and shows clearly that not only the particular numbers, but the whole approach can be changed. We’ll be paralleling his alternative proof here.

Morris wrote back:

Dear Doctor Peterson, Thank you for your comments and also for the library references, which I have already printed out but not yet read completely. Concerning this business about, "the bounds on the slope of the function in the neighborhood of the point under consideration will play a large role in determining what delta will look like," this is what I am thinking at this point: Let a particular situation be: the limit of f(x) = x^2+1 as x approaches 2 is 5 with epsilon = 1 and delta = 1/5. Now the neighborhood of the point 2 is (1.8,2.2) and the corresponding neighborhood of 5 is (4.24,5.84). The slopes of f corresponding to the endpoints of the neighborhood of 2 are 3.6 and 4.4. So 3.6*1/5 = 0.72 and 5-4.24 = 0.76 are nearly the same. Also 4.4*1/5 = 0.88, which is not far from 0.84. Has this got something to do with what it's about? Propagation of errors through functions?

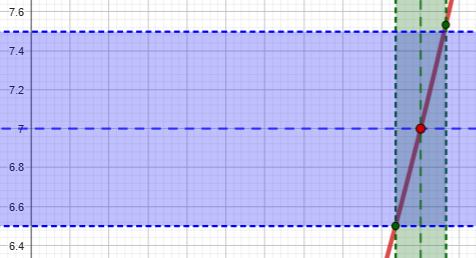

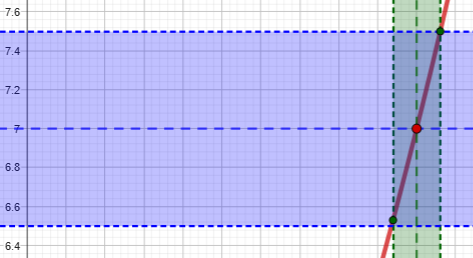

Here we see his neighborhood for y in purple (showing that it is within the blue \(\epsilon\)-neighborhood):

The segments PQ and QR can hardly be distinguished from the curve, so I’ve extended them into green and blue lines. But you can easily see that P is closer to the line \(y=5\) than is R, because that side is less steep. As a result, it is R that we need to be sure stays within the epsilon-bounds.

I replied:

Hi, Morris.

Yes, what you describe is what I had in mind. More precisely, the ratio of epsilon to delta will be, at least in "nice" cases like this, no more than the slope of the steepest chord from the limit point to points in the neighborhood. Because the parabola under consideration is smooth, with its slope either increasing or decreasing as you move away, this steepest chord will be at an endpoint of the interval:

R

+-------------------+ f(2)+e = f(2+d)

| /|

| / |

| / |

| / * |

| / |e

| / |

| / * |

| / |

| Q/* |

+---------+---------+ f(2)

| /* | |

| / * | |

P+ * - - - | - - - - | f(2-d)

| | |

| | |e

| | |

| | |

| | |

| | |

+---------+---------+ f(2)-e

| d | d |

2-d 2 2+d

This is a case where an exaggerated sketch can be a little clearer than the exact graph!

In this example, we can just find d (delta) for a given e (epsilon) by solving

f(2+d) = f(2)+e

and then showing that, because of the way f curves, f(x) will be within e of f(2) whenever x is within d of 2. The ratio e/d is the slope of chord QR, which is between the slope of f at Q and the slope at R.

Note that here we are solving for the ideal (largest possible) delta, which will take more work than the proof we were looking at until now – but, though not necessary, can be instructive.

For our problem, with \(f(x)=x^2+1\), this amounts to doing what Doctor Rob did in that “second link” mentioned above, and solving for delta: $$f(2+\delta)=f(2)+\epsilon\\(2+\delta)^2+1=(2^2+1)+\epsilon\\\delta^2+4\delta-\epsilon=0\\\delta=\frac{-4\pm\sqrt{16+4\epsilon}}{2}=-2\pm\sqrt{4+\epsilon}$$

We need to take the positive sign to get a positive delta, \(\sqrt{4+\epsilon}-2\).

Other functions are not as simple, and we can't find the greatest possible delta so precisely; but we approximate this by making various simplifications. You could probably, in many cases, at least make a good guess at delta based on slope considerations, and then proceed to prove your conjecture algebraically. Of course, you realize that there is not just one delta we can use; any delta LESS than the "ideal" delta we found will satisfy the definition of a limit.

Morris was satisfied.

What if epsilon is, say, 0.05?

Eleven hours later on the very same day, we got this question about another equivalent limit, this time starting out with a specific (smaller) value for epsilon and finding the ideal delta:

Definition of the Limit I need some help with the definition of the limit, particularly choosing delta for a given epsilon. For example, consider the limit as x approaches 2 of (x^2 + 3) = 7 with epsilon = .05. Here is my work: |x^2 + 3 - 7| < .05 |x^2 - 4| < .05 -.05 < x^2 - 4 < .05 3.95 < x^2 < 4.05 1.98746... < x < 2.01246... -.01253... < x - 2 < .01246 The lower and upper values for delta are different, so how do I choose which one should be delta? I seem to remember reading that the smaller value is usually chosen, so delta would equal .01246. However, I can find no explanation as to why the smaller value is chosen. Is there anything wrong with saying that delta equals .01253? Is one value considered more correct than the other, or are they both considered correct? Moreover, on a test should .01253 be considered a correct answer? Any help is greatly appreciated.

This, again, is equivalent to our original limt: if \(\displaystyle\lim_{x\rightarrow 2}x^2=4\), then \(\displaystyle\lim_{x\rightarrow 2}x^2+3=7\), and vice versa.

I can’t show Stephen’s numbers on a graph, because the intervals would be barely visible!

But his work can be generalized to any epsilon, which will, with a final adjustment, constitute a new proof of the limit: $$-\epsilon<x^2-4<\epsilon\\4-\epsilon<x^2<4+\epsilon\\\sqrt{4-\epsilon}<x<\sqrt{4+\epsilon}\\\sqrt{4-\epsilon}-2<x-2<\sqrt{4+\epsilon}-2$$

All that’s missing is to pick a delta that will work …

I answered this one, too:

Hi, Stephen. Any number is acceptable if you can PROVE that it fits the definition; you can't just look at an inequality and say "I seem to recall that this one will work." So let's see whether it is true that, whenever |x-2| < 0.01253, we will have |x^2-4| < 0.05. For a quick test, we can just try making |x-2| = 0.01252 and see if it works. In one direction, we have x = 2.01252, x^2 = 4.0502367504, and x^2-4 = 0.0502367504. This is NOT less than 0.05, so we see that it doesn't work.

So we’ve proved that this particular delta doesn’t work. We need to prove that the other does.

Now, how could we have thought through this to see why we should choose delta as 0.01246? Look back at what you found:

-.01253 < x - 2 < .01246

You showed that this is equivalent to |x^2 - 4| < 0.05 (given that x > 0). You want to choose a delta so that this will be true whenever |x-2| < delta. Notice that the latter is the same as

-delta < x - 2 < delta

The interval we want is symmetrical; that is, it extends the same distance (\(\delta\)) on either side of \(x=2\). The interval we need to satisfy for epsilon is not symmetrical.

If you pick delta = 0.01246, then this interval is inside the interval from -0.01253<x-2<0.01246, so that any x within delta of 2 does what you want.

If you choose delta = 0.01253, then

-0.01253 < x - 2 < 0.01253

does NOT imply

-0.01253 < x - 2 < 0.01246

because the former includes some numbers that are not in the latter.

So we pick the smaller of the two possible deltas, in order to fit inside. That’s the quick answer to his question!

Do you see how the reasoning goes? Essentially we want a symmetrical interval that is INSIDE the interval equivalent to the epsilon goal, so that x being within delta IMPLIES that f(x) is within epsilon. So we can choose any delta LESS THAN OR EQUAL TO 0.01246.

Visualizing it

Let’s use larger numbers, so we can see them. Rather than use \(\epsilon=0.05\), I’ll take \(\epsilon=0.5\). Replicating Stephen’s work, we have $$-0.5<x^2-4<0.5\\3.5<x^2<4.5\\1.8708…<x<2.1213…\\-0.1292…<x<0.1213…$$

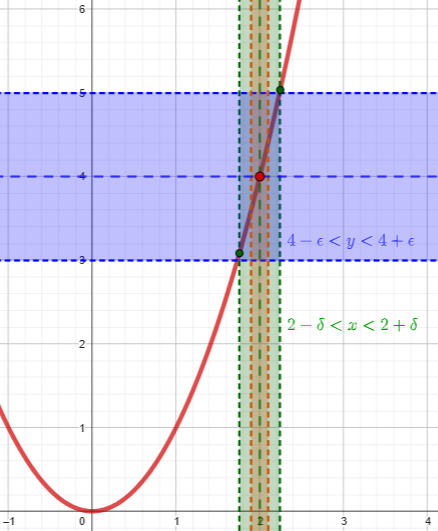

Here is the graph using \(\delta=0.1292\):

Note that the function values when x is within the delta-interval are not all inside the epsilon interval; the upper end is outside.

Here is the graph using \(\delta=0.1213\):

This time y is within epsilon whenever x is within delta.

So this value of delta works. In fact, this is the largest delta that can work.

What would it look like if we used the value from our original proof, \(\displaystyle\delta=\frac{\epsilon}{5}\)? It would be \(\displaystyle\delta=\frac{0.5}{5}=0.1\):

Once again, we are reminded that we don’t need the optimal delta that Stephen has found, just one that works; and in the original proof, our restriction to (1, 3) made it easy to guarantee a delta that works, without needing square roots (or, indeed, to be able to solve at all). And that is what the proof is all about!

Making it a proof

Let’s try to finish our Stephen-style proof. So far, we have this: $$-\epsilon<x^2-4<\epsilon\\4-\epsilon<x^2<4+\epsilon\\\sqrt{4-\epsilon}<x<\sqrt{4+\epsilon}\\\sqrt{4-\epsilon}-2<x-2<\sqrt{4+\epsilon}-2$$

Now we have two candidates for delta, namely $$\delta_1=|\sqrt{4-\epsilon}-2|=2-\sqrt{4-\epsilon}$$ and $$\delta_2=|\sqrt{4+\epsilon}-2|=\sqrt{4+\epsilon}-2.$$ With a little thought (such as sketching a graph!) we can see that the smaller of the two is \(\delta_2\).

That was the exploration step, deciding what to use for \(\delta\), and didn’t require proof. And this is the same delta obtained in that “second link” by a different method.

Now we can write the actual proof:

Given any \(\epsilon\), let \(\delta=\sqrt{4+\epsilon}-2\). Then whenever \(0<|x-2|<\delta\), we have

$$2-\delta<x<2+\delta\\2-(\sqrt{4+\epsilon}-2)<x<2+(\sqrt{4+\epsilon}-2)\\4-\sqrt{4+\epsilon}<x<\sqrt{4+\epsilon}$$

Now we need to think a little. If both bounds on x are positive, then we can square the inequality. But \(4-\sqrt{4+\epsilon}<0\) if \(\epsilon>12\). To avoid this problem (since we really only care about small values of \(\epsilon\) anyway), if we were given an \(\epsilon>12\), we could just replace it with, say, \(\epsilon=1\) in calculating \(\delta\). So we can assume both bounds are positive.

Now we can square: $$(4-\sqrt{4+\epsilon})^2<x^2<(\sqrt{4+\epsilon})^2\\16-8\sqrt{4+\epsilon}+(4+\epsilon)<x^2<4+\epsilon\\20+\epsilon-8\sqrt{4+\epsilon}<x^2<4+\epsilon\\16+\epsilon-8\sqrt{4+\epsilon}<x^2-4<\epsilon$$

In order to conclude that \(|x^2-4|<\epsilon\), we need to show that \(16+\epsilon-8\sqrt{4+\epsilon}>-\epsilon\). But this is equivalent to \(16+2\epsilon>8\sqrt{4+\epsilon}\), which, since both sides are positive, is equivalent to \((8+\epsilon)^2>(4\sqrt{4+\epsilon})^2\), that is, \(64+16\epsilon+\epsilon^2>16+16\epsilon\), so that \(48+\epsilon^2>0\), which is true. (Reverse this sequence to see the proper proof.)

This completes the proof. I think the usual proof is a lot easier!

Pingback: How to Question a Proof, and Find Answers – The Math Doctors