Having looked at geometrical transformations, we can now apply them to the idea of symmetry. We’ll focus on symmetry of figures in a plane.

What is symmetry?

We’ll start with this question from 1996, which provides a nice general definition of symmetry:

Axes of Symmetry Can you give me guidance on how to explain axes of symmetry to a year 5? My son had some trouble with it and I'm not sure as a parent how to explain in an intuitive way. Also, the correct answer to one question puzzled me a bit: a triangle was said to have three axes of symmetry, but it seems to me that this is only true for an equilateral triangle. By the way, my basic definition of an axis of symmetry is that it joins points on the perimeter in such a way that it divides the figure into two identical figures. I've checked the archives but couldn't find anything that seemed right for the level.

(John is right about triangles; the question may have had tricky wording.)

Doctor Ceeks explained, generalizing the question:

Symmetry is a very broad concept. I might try to explain it like this. Suppose you have an object, like a triangle. Suppose you're with a friend, and the friend leaves the room for the moment. While your friend is gone, you do something to the object... you move it, flip it, spin it, or something, in such a way that when your friend comes back, your friend can't tell the difference and has no idea you did something to the object. Then you've discovered a symmetry of the object. Now, if you rotated the object about an axis (like the earth spins on an axis), then there's an "axis of symmetry."

This is the general idea of symmetry: a transformation of an object that results in an image identical (not just in shape, but in position) to the original. For example, he might put a square on the table, and I rotate it 90° about its center. It will look as if I’d done nothing. That means it has 90° rotational symmetry. Or, I might flip it around a vertical line through its center (keeping in mind what we saw previously, that we’re assuming it’s the same on both sides so the flipping is equivalent to reflecting it). Again, it will look as if I’d done nothing; it has mirror symmetry about the vertical axis.

Here are the original square, the rotated square, and the flipped square (honest!):

For a two-dimensional object, an axis of symmetry is a line about which we can flip, or reflect, the object; in three dimensions, it would be associated with rotational symmetry. We’ll see both below.

Many kinds of symmetry

For more depth, consider this question from 1997, which asks about one kind of symmetry, but leads to others:

Rotational Symmetry I am looking for a precise definition of rotational symmetry of a figure in a 2-dimensional plane. I have checked in three different geometry books here in our district and they have different explanations and are somewhat contradictory. 1) According to one of the books, if a figure has one line of symmetry, it has rotational symmetry somewhere between 0 and 360 degrees. But where does that leave the isosceles trapezoid? The isosceles trapezoid does have one line of symmetry, but does not have rotational symmetry until it has rotated 360 degrees, which does not fit the definition. 2) Another book says a figure has rotational symmetry if it "looks the same." What kind of math definition is that? This is an 8th grade textbook that I am using in an advanced 7th grade pre-algebra class. 3) The geometry teacher here says he doesn't even use those two terms in connection with each other because symmetry and rotation are not interrelated. These kids are sharp and ask some high level questions. Can you help us out with this rotational symmetry idea?

The first answer, from a book, makes no sense to me; I’d want to see the context, which may involve three dimensions. The second, as we’ll see, makes a lot of sense when some context is added in. The third is probably based on a restricted idea of symmetry, thinking only about reflection (line) symmetry and forgetting about rotational symmetry. We’ll see both.

What is symmetry?

Doctor Tom answered by starting with the most general definition:

Hi Beth, Actually, definition 2 is probably the most useful, if it's stated correctly. In general, an object is "symmetric" if it "looks the same" after it has undergone some transformation or operation. Here's a more precise definition: an object (a set of points in the plane) has symmetry if you can find some transformation such that the set of points before the transformation is the same set as the set of points after the transformation. So we might say "looks exactly the same." Said another way, an object X has symmetry if there exists a non-trivial transformation T such that X = T(X).

Note the close connection of symmetry with transformations.

Line (reflection, mirror) symmetry

And you're right - line symmetry doesn't imply rotational symmetry. Let's look at some simple symmetries first. For example, you can have reflection or mirror symmetry if the object looks the same after being reflected in a mirror. A human is (roughly) mirror-symmetric, since our left and right sides are pretty much the same. In other words, if I took a photo of a person and showed it to you, you would have a hard time telling me whether I had taken a photo of a person, or of a person's image in a "perfect" mirror, right?

People, of course, are not exactly symmetrical; not only can can we have hair that goes to the left or the right, but our internal organs are asymmetrical – and (almost) always oriented in the same way, even for left-handers. Not to mention that we can pose in asymmetrical ways!

This kind of symmetry is also called line symmetry, because it involves reflection in a line:

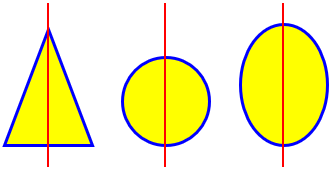

An isosceles triangle is mirror symmetric, but a triangle with sides of three different lengths is not. A circle is mirror symmetric, as is an ellipse. An interesting exercise is to look at the upper-case letters of the alphabet to see which ones are mirror symmetric. I get: A B C D E H I M O T U V W X Y (Note that sometimes the mirrors are on the right of the letters and sometimes on the tops (or bottoms) to get the same reflected image.)

These have symmetry:

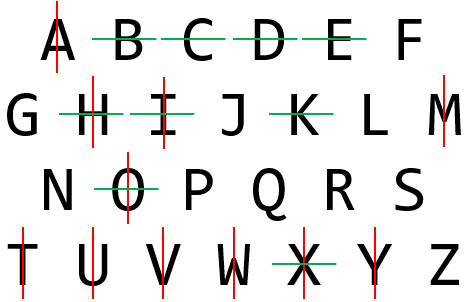

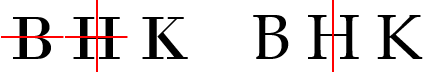

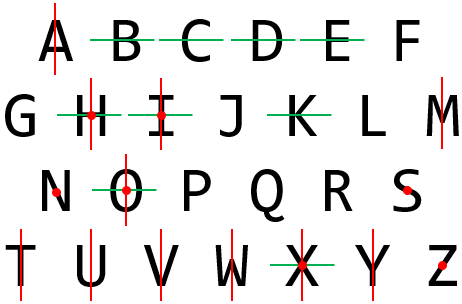

Here we see all the letters, with lines of symmetry where possible:

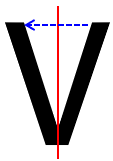

Some letters have a vertical line of symmetry, others horizontal, and others both; we see that in the letters H, I, O, and X. And some letters (N, S, and Z) seem symmetrical in another way we’ll look at later.

When we talk about the symmetry of letters, we generally assume they are written in a maximally symmetrical way, as in the font (Consolas) that I used above. For example, you can make an H with the horizontal line higher or lower than the middle, which would destroy the horizontal line symmetry; and a font with serifs, or a slant, may lose symmetry. Doctor Tom may have omitted K because he had in mind a font like those below.

Here, for example, are some letters that ought to have symmetry in a horizontal line, but do not in this font (Trebuchet):

Serifs may or may not break symmetry:

And forget about symmetry in a calligraphic font!

If you reflect the other letters, it looks as if they have been drawn by someone with dyslexia.

Rotational (radial) symmetry

But "reflecting in a mirror" is just one operation you can do to objects. How about rotating them by 180 degrees? Which ones look the same after that? I get: H I N O S X Z These are symmetric under a 180-degree rotation.

Here we can see the rotations:

This 180-degree rotational symmetry is also called point symmetry, which we’ll look at later. We’ll also relate it to the reflection symmetry that some of these letters have (H, I, O, X), but not others (N, S, Z).

Some things are symmetric under a 90-degree rotation: squares, for example. In fact, squares have a bunch of symmetries - they are also symmetric under a 180-degree rotation, or under a reflection.

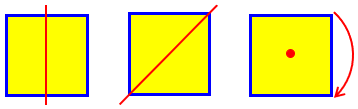

Here are some of the symmetries of a square:

This is also called four-fold rotational symmetry, because 4 rotations bring the object back to its original position.

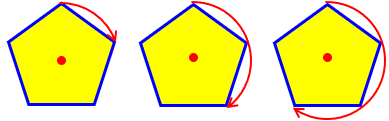

In general, we can have n-fold rotational symmetry for any integer \(n>1\):

A perfect pentagon is symmetric under a 72-degree (1/5 turn) rotation (or 144-degree rotation, or a 216-degree rotation, etc.). A polygon with 127 equal sides and angles has symmetry under a rotation of 1/127 turn (or 2/127 turn or 3/127 turn, ...).

Some letters, (like F, G, P) don't have any standard geometric symmetries.

Reflections and rotations of these never look the same as the original.

Rotational symmetry, more broadly

Usually, in mathematics, "rotational symmetry" means that ANY rotation leaves the object looking (exactly) the same. On a plane, there aren't many things that are rotationally symmetric - circles are, or sets of circles with a common center.

This refers to full rotational symmetry. As the circle rolls, it always looks the same, whatever angle it has turned.

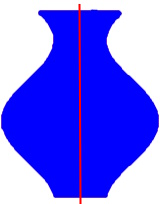

In three dimensions, however, there are thousands of interesting objects with rotational symmetry. Imagine taking any wire shape (bent however you like), holding the two ends, and spinning it so fast that it's a blur. The shape of that blur will have rotational symmetry. Common examples are spheres, cylinders, cones, tori (doughnut shapes), etc.

This is also called axial symmetry, where we are rotating around an axis in space, rather than a point on the plane. Here is a typical example (picture from Wikipedia):

Curiously, the same term is often used of reflection symmetry in the plane, thought of as reflection around an “axis”, which is the same as 180° rotation around that axis. A cross-section of our figure through the axis would have such symmetry:

This may account for some of the confusion about reflection and rotational symmetry.

Symmetry beyond geometry

Although it's not obvious from a 7th grader's point of view, symmetry is so important that huge areas of mathematics are basically devoted to the study of symmetry. For example, the equation: x^2 + y^2 + z^2 + xyz is symmetric in the variables, because if you jumble them around (put in x where you see y and y where you see x, for example), the equation is exactly the same. Or maybe a better way to look at it is this: if x, y, and z are three numbers, 3, 5, and 11, but you can't remember which is which, for symmetric equations it doesn't matter. However you decide to match them up, you'll get the same numerical result. The "object" is the equation; the operation is to jumble the variables. After the jumbling, the equation is exactly the same (well, the terms may be in a different order, but the numerical value is the same).

We’ve discussed symmetric polynomials here.

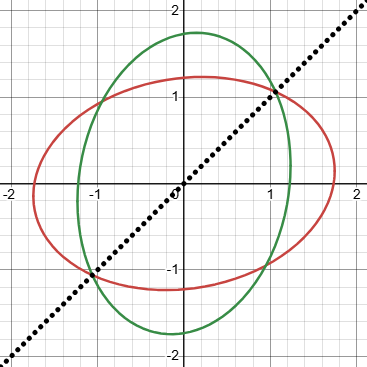

Interchanging variables in an equation is like a reflection. For example, using only two variables, if we swap variables x and y in the equation \(3x^2-xy+6y^2=9\), the red curve here, we get \(3y^2-yx+6x^2=9\), the green curve, which is reflected over the line \(y=x\):

The equation \(3x^2-2xy+3y^2=9\) is symmetric, so it is its own reflection:

And not just mathematics - physics too. Imagine the collision of two perfect balls - they come in, hit each other, and bounce off in different directions. Imagine taking a film of such a collision, and playing it backwards. Would the physics still be correct? Yes! Elastic collisions are symmetric with respect to "time reversal" - it's a weird concept, but it does fit the general definition - the object (the physical laws of elastic collisions) are symmetric if you look at them with time going backwards. This is just scratching the surface, but most other symmetries in physics are even more bizarre.

If you played a movie of a perfect collision backward, it would look normal; a ball bouncing and losing energy would look all wrong when played backward, as it would be coming out with more energy.

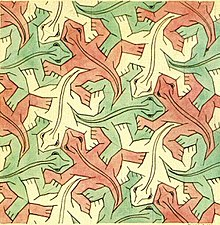

You may be wondering whether other transformations (translation, glide reflection) can produce symmetry. They can; but the result is necessarily an infinite figure, since repeating a translation eventually goes infinitely far. We don’t have any questions about that at this level; but the subjects of “wallpaper patterns” and “frieze patterns” relate to this.

Here are examples of a wallpaper and a frieze, where you have to imagine the same arrangement repeating forever:

Point and line symmetry

Here is a 1997 question:

Point and Line Symmetry in the Alphabet The question was to examine the letters of the alphabet to determine which ones have point symmetry, line symmetry, or both. How many letters have neither form of symmetry? I understand the idea of line symmetry and have identified the letters A, B, C, D, E, H, I, M, O, T, U, V, W, X, and Y as having line symmetry. If I understand point symmetry correctly then O and possibly X are the only letters that have both point and line symmetry. This would leave F, G, J, K, L, N, P, Q, R, S, and Z, for a total of 11 letters, that have neither point nor line symmetry. Am I correct?

Nancy missed K, possibly by not having used the most symmetric form. She also missed some with point symmetry.

Line symmetry is the reflection symmetry we’ve already seen, reflecting across a line:

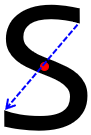

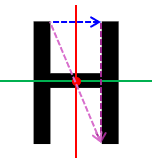

We haven’t yet talked about point symmetry specifically, though we’ve mentioned that (in a plane) it is the same as 180° rotational symmetry. What it really means is “reflection” in a point:

It’s hard to think of this as reflection in the usual sense, but the “image” is the same distance on the other side of the point, just as reflection in a mirror is the same distance on the other side of the mirror.

Doctor Tom answered:

Hi Nancy, There are some letters that have point symmetry and not line symmetry: N, S, and Z. Consider the point in the center of each of those letters - halfway down the diagonal lines of the N and Z, and right where the S starts to curve the other way. You can reflect any point on those letters through that center point, and be back on the letter.

Let’s add the points to our alphabet:

Notice that there are more than just N, S, and Z with point symmetry.

In addition to O and X that have both point and line symmetry, the letters H and I also have both forms. In fact, you will note that the letters that have both point and line symmetry actually have two lines of symmetry - in this case both a horizontal and vertical line passing through the center of the letter. It turns out that any figure with two different lines of symmetry will also have point symmetry.

Can you see why this last statement is true? If you do the two (perpendicular) line reflections, that composition of two reflections ends up being a point reflection:

Last time, we saw how the composition of two reflections in intersecting lines is a rotation by twice the angle between the lines; that’s what happened here! The lines are at a 90° angle, so the rotation is 180°.